The Singing Life of Birds. The Art and Science of Listening to Birds

The Singing Life of Birds. The Art and Science of Listening to Birds

Houghton-Mifflin Co.

Hardcover, 2005; ISBN 0-618-40568-2

Softcover, 2007; ISBN-13: 978-0-618-84076-2

482 pages

Winner of the 2006 John Burroughs Medal award for outstanding natural history writing, winner of the 2006 American Birding Association’s Robert Ridgway Award for excellence, “the Best of the Best in Published Scholarship” (Critics’ Choice) ; as featured on the radio, on NPR’s Fresh Air with Terry Gross, on NPR’s and National Geographic’s Radio Expeditions, Earthwatch Radio, and Kojo Nnamdi Show. And as featured in Audubon Magazine (and a second time) Scientific American, USA Today, Entertainment Weekly, Outside Magazine, E Magazine, and elsewhere.

What readers are saying: This book is truly a gem, that rare marvel, one of the very best bird books I’ve ever read, one of the best, most enthusiastic and enlightening books about how real science is done, and it reads like a cross between a mystery novel and lovely poetry. Kroodsma, as both scientist and storyteller, takes us repeatedly into the field, into the birds’ world. He peels away the mystery of birdsong without casting off its mystique, and will change forever the way each of us listens. This book is an eye-opener, an ear-opener, and a mindblower, a family treasure, a true work of art, a superb masterpiece, a tour de force, a wonderful gift to the world.

1) Preface

2) Table of Contents

3) Readers are saying

4) Full length reviews

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

1) Preface

Somewhere, always, the sun is rising, and somewhere, always, the birds are singing. As spring and summer oscillate between the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, so, too, does this singing planet pour forth song, like a giant player piano, in the north, then the south, and back again, as it has now for the 150 million years since the first birds appeared.

and somewhere, always, the birds are singing. As spring and summer oscillate between the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, so, too, does this singing planet pour forth song, like a giant player piano, in the north, then the south, and back again, as it has now for the 150 million years since the first birds appeared.

Ten thousand species strong, their voices and styles are as diverse as they are delightful. Some species learn their songs, just as we humans learn to speak, but others seem to leave nothing to chance, encoding the details of songs in nucleotide sequences in the DNA. Of those that learn, some do so only early in life, some throughout life; some from fathers, some from eventual neighbors after leaving home; some only from their own kind, some mimicking other species as well. Some species sing in dialects, others not. It is mostly he who sings, but she sometimes does, too. Some songs are proclaimed from the treetops, others whispered in the bushes; some ramble for minutes on end, others are offered in just a split second. Some birds have thousands of different songs, some only one, and some even none. Some sing all day, some all night. Some are pleasing to our ears, and some not.

It is this diversity that I celebrate. How the sounds of these species differ from each other is the first step to appreciating them, of course, but those questions quickly give way to “why” questions. Why do some learn and others not? Why do dialects occur in some species and not others? Why is it mainly the male who sings? It is these and similar “why” questions that so intrigue us biologists as we try to understand the individual voices that contribute to the avian chorus.

In writing about our singing planet, I can focus on only a few of its voices. The thirty stories told here are personal journeys, ones that I have traveled over the past thirty years in my quest to understand the singing bird.

Many are based on my own research and are years in the making. Others are based on just several days’ experience, or even less, as I seek out birds that illustrate the research of friends and colleagues who share my passions. No matter the source, each story is based on listening and on learning how to hear an individual bird use its sounds, and each story illustrates some of the fundamentals of the science called “avian bioacoustics.” Together, I hope these stories and their sounds reveal how to listen, the meaning in the music, and why we should care.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

2) Table of Contents

“The earth has music for those who listen.” –William Shakespeare

Preface ix

Acknowledgments xi

1. Beginnings 1

Hearing and seeing bird sounds 1

The Bewick’s wren 10

The American robin 23

Good listening, good questions, this book 37

2. How songs develop 42

Learning songs: where, when, and from whom 44

The white-crowned sparrow 44

The song sparrow 55

Borrowed songs–mimicry 68

The northern mockingbird 68

Songs that aren’t learned 79

Tyrant flycatchers–Alder and willow flycatchers, eastern phoebe 79

Why some species learn and others don’t 89

The three-wattled bellbird 89

The sedge wren 102

3. Dialects. How and why songs vary from place to place 119

The great marsh wren divide 120

The black-capped chickadee 135

The chestnut-sided warbler 145

Travels with towhees, eastern and spotted 157

The tufted titmouse 165

4. Extremes of male song 177

Songbirds without a song 179

The blue jay 179

Songbirds with especially complex songs 191

The brown thrasher 191

The sage thrasher 202

The winter wren 214

Songbirds with especially beautiful songs 225

The Bachman’s sparrow 225

The wood thrush 237

The hermit thrush 255

Music to our ears 267

Songs on the wing 276

The American woodcock 276

Tireless singers 287

The whip-poor-will 287

The red-eyed vireo 297

5. The hour before the dawn 304

The eastern wood-pewee 304

Chipping and Brewer’s sparrows 313

The eastern bluebird 325

6. She also sings 335

The barred owl 336

The Carolina wren 346

The northern cardinal 357

Appendix I: Bird Sounds on the Compact Disc 366

Appendix II: Techniques 402

Appendix III: Taxonomic List of species names 411

Notes and Bibliography 415

Index 452

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

3) Readers are saying

“Don Kroodsma has the soul of a poet and the mind of a scientist, and he understands birdsong better than the birds do themselves. In this book he gives us a fascinating inside look at some of nature’s most beautiful mysteries.”

— Kenn Kaufman, author of Kaufman Field Guide to Birds of North America

Donald Kroodsma may be the world’s best listener. He is also intensely inquisitive (and a darn fine writer). He yearns to know not just what bird species he hears singing, but what individual bird it is and why it is singing what it is singing. This engaging and amazing sense-filled journey takes you inside the minds of both the author and his beloved songsters. . . . Don Kroodsma is both scientist and storyteller as he recounts a life spent listening to birds as individuals. After reading The Singing Life of Birds, you’ll listen to birds with new ears.

–Bill Thompson III, editor, Bird Watcher’s Digest

“Don Kroodsma has done what few scientists are able to do, and that is condense his life’s work into a true work of art . . . I greatly applaud his effort and believe it stands out among all such efforts as being the best introduction to the study of bird song ever produced.”

–Lang Elliott, author of Common Birds and Their Songs and Music of the Birds

“Kroodsma’s clear prose, his apparent joy in his work, and the sweep across countries and continents will make bird song lovers out of even the most tin-eared. Our entire family are converts.”

–Jane Yolen, author of Owl Moon, Bird Watch, Wild Wings, and Fine Feathered Friends

“. . . my 9 yr old daughter, my 7 yr old son, and I all listened to the CD and read through some of the book today. I was thrilled with their excitement when they recognized bird calls that we had identified last year in our back yard. . . . what a treasure this book has already become in our family.”

–Heather, Mother of future naturalists

With all due respect to rainbows and sunsets, birdsong is the most endearing, the most bewitching, aspect of Nature. . . . In this engaging volume, Donald Kroodsma peels away the mystery of birdsong without casting off its mystique.

–Ted Floyd, editor, Birding

” The combination of science and wonder, all from the mind of a master ornithologist, reminds me of Aldo Leopold, Peter Matthiessen, and Steven Jay Gould.”

–(the late) David Stemple, birder

This book will have a special place on my shelf. For Donald Kroodsma the study of birdsong is not merely a vocation but a passion; and his passion is communicated to the reader on every page through colourful field notes and ingenious listening experiments.

The book is an ear cleaning exercise. If everyone could learn to listen as carefully as Dr. Kroodsma and his colleagues, the soundscape of the world would be a lot more beautiful and less noise-riddled than it is today.

–R. Murray Schafer, Musician and composer

The Singing Life of Birds will change forever the way each of us listens to bird song. Not only will we have better techniques for listening (Who knew we could listen with both our ears and our eyes?), but we will know how to listen for the interaction between the singers, how to listen to the community of birds. What a gift to birders, naturalists, and anyone who enjoys the outdoors.

–Mary Alice Wilson, birder

My short list of thrilling, melodic, world-class composition has lengthened. The bird composers join Bach, Beethoven, Chopin, Mozart and Schubert. Like the finest of strict, yet personable, maestros Don Kroodsma teaches us avian Earth symphonics. I do not tire of the aural sensations, the tunes, rhythms, preludes and flourishes, the twittering surprises. This musical delight on CD, never passé, along with his charming verbal description brings us ever closer to understanding how and why both Nature and her music remain so important to our lives.

–(the late) Lynn Margulis, Distinguished University Professor, Dept of Geosciences, UMass Amherst

A tour de force. “The Singing Life of Birds” is an encyclopedic chronicle of a lifetime of adventure in the musical realms of the greatest vocalists on planet Earth: our songbirds. Dr. Kroodsma’s lyrical writing resounds with the inspiration of the beauty, the magic and the mystery of these birdsongs which have become part of his soul . . . a wonderful gift to the world.

–Paul Winter, Saxophonist, composer and bandleader, explorer of the world’s musical traditions, and founder of Living Music.

“It has been said that bird song is the poetry of earth, a sentiment I have always shared. No other animals have such complex and beautiful songs as birds do. For this reason they have been celebrated for hundreds of years. Don Kroodsma’s book, THE SINGING LIFE OF BIRDS, takes us deeper into this marvelous phenomenon and addresses such questions as why birds sing, how an individual bird acquires its songs and why some birds develop such complex and beautiful songs. Besides the knowledge this book will yield to the reader I especially recommend it in the expectation that persons who read it will listen longer to the songs of individual birds, both to understand them and to appreciate them. Such activity will enrich the life of anyone who does so.”

–Victor Emanuel, Founder of Victor Emanuel Nature Tours

“Say, there’s a new book that every serious birder will enjoy. It’s The Singing Life of Birds, by Donald Kroodsma. The sonagrams (created with the Cornell Lab’s Raven software) are so beautiful that they could be calligraphy. I mean, it’s framable art. Kroodsma says he listens with his eyes . . . this book is an eye-opener, an ear-opener, and a mind-blower. I heard a whole new robin before dawn this morning, and I’ll never hear them the same old way again. . . . It’s a thrilling book.”

–Diane Porter, Iowa Ornithologists’ Union listserv

A Superb Masterpiece . . . Reading the book took me on a journey into an amazing, beautiful, and complex world that I previously had no idea existed. I kept finding myself saying “wow!” at the wonderful and startling discoveries I came across. I especially liked the fact that the author is completely honest about what he doesn’t know, explaining the many mysteries about bird singing that still remain to be solved. Rarely does one see the humanities so beautifully merged with science. The book is one of the best I have ever read, barring none.

–Peter Baum, July 2005

. . . one of the best, most enthusiastic and enlightening books about how real science is done . . . You will never listen to that robin chirping on your lawn the same way again.

–Mark Lynch, WICM Public Radio

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

4) Full Length Reviews

a) Birder’s World

b) The Living Bird

c) Midwest Book Review

d) Wilson Journal of Ornithology

e) Journal of Field Ornithology

f) Bird Watcher’s Digest

g) Scientific American

h) Birdchat

i) The Bird Observer

j) Critics’ Choice

k) Publisher’s Weekly

m) Library journal

n) Birdwatching.com

4a) Birder’s World

August 2005

Review by Eldon Greij

The Singing Life of Birds: The Art and Science of Listening to Birdsong by Donald Kroodsma, Houghton Mifflin, 2005, 448 pages, $28, hardcover, includes CD of birdsongs.

Every once in a while, a book appears that is truly a gem, and this is one. Donald Kroodsma’s treatment of birdsong and the singing behavior of birds is extraordinary. Anyone with an interest in birds – from casual birdwatchers to serious birders, from armchair naturalists to scientists – will enjoy it. And no one is more qualified to write about the subject than Kroodsma, an ornithologist who in 2003 received the prestigious Elliott Coues Award the American Ornithologists’ Union for his significant contributions to avian research. His citation called him the “reigning authority on the biology of avian vocal behavior.” Equally important, Kroodsma has the ability to describe complex events in an engaging, lucid, clear manner. He has a magical way with words.

Both his career and this book began in his Oregon backyard over 30 years ago, when he listened to singing Bewick’s Wrens and asked a simple yet complex question: “How do they learn their songs?” That question led to others, and a lifetime of work. Why are some birds’ songs simple, while others are complex? Why do some birds repeat phrases over and over before switching to other songs, while others do not repeat. Why do some birds learn all of their neighbors’ songs? Why do some birds sing at night? The questions go on and on.

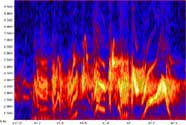

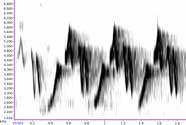

In the years since Kroodsma pondered the singing wrens, he has listened to countless birds, recorded and analyzed their songs, and tried to make sense of it all. One aspect of his work that makes it so different is the intensity with which he studies the songs of individual birds. In many cases, he knows every variation in a bird’s repertoire. He asks questions and proposes methods to get answers, cleverly bringing his readers along as he leads them through the auditory maze. It’s as if we are part of his research team. Analyzing birdsong in such detail requires the study of sonograms, visual presentations of sound created when frequency is plotted as a function of time. Kroodsma calls them “musical scores for birdsong” and describes their preparation and interpretation in detail and with clarity. Sonograms accompany all species discussed in the text. An audio CD, included with the book, contains all the songs from which the sonograms were made, enabling readers to listen to the sounds as they see them.

Kroodsma describes singing behavior and song structure, in detail for 30 species and makes comments about a dozen others. His book is divided into six broad chatters. The first, “Beginnings,” offers an in-depth vocal treatment of Bewick’s Wren and the American Robin. The other chapters are “How Songs Develop” (learning songs, mimicry, and songs that aren’t learned), “Dialects” (how and why songs vary from place to place), “Extremes of Male Song” (songbirds without a song and songbirds with especially complex or especially beautiful songs), “The Hour Before the Dawn” (the fascinating and puzzling dawn chorus), and “She Also Sings” (female birds that sing).

Consider the song of a common bird, the ubiquitous American Robin. It has a beautiful song that most of us have heard for years. We generally describe it as a series of mostly three-syllable phrases, such as cheerily, cheerio, cheeri-up, cheerio. But most robins have a dozen or more different phrases that most of us miss. And what about the high-pitched, whispered hisselly phrase? Have you heard it?

Consider also the Chestnut-sided Warbler. At about 4 a.m., Kroodsma is on a ridge in the Berkshires, facing a power-line cut that runs east, down a valley, and up to the next ridge half a mile away. He walks that cut and, along the way, listens to 22 male Chestnut-sided Warblers on territories. But the warblers are not singing the classic pleased-pleased-pleased-to-MEETCHA song that we have learned to associate with the warblers. They’re singing warbled “battle songs,” intended to keep other males out of their territories. Each bird’s battle song is different, so each male has a unique marker. Just before sunrise, however, the concert changes: The warblers switch to the MEETCHA songs. Their intent changes from excluding males to attracting females. And MEETCHA songs are similar; only four variations are shared by all males. The significance of this and much more comes out in Kroodsma’s text.

While listening to Marsh Wrens, Kroodsma confirmed that birds from the West sang differently than those from the East. The difference was pronounced. And western birds had a larger repertoire (more than 100 songs) than those of the East (fewer than 50 songs). The Marsh Wren is considered to be one species, but Kroodsma wasn’t so sure. He sought mid-continent areas where the two forms overlapped and found them in Nebraska and Saskatchewan. Standing in marshes there, he heard songs that were either classic eastern or western. That was strange: If the Marsh Wren is indeed one species, he reasoned, the two forms should interbreed in areas of overlap and variations of songs should be heard, yet he heard none. This mystery unfolds in the book.

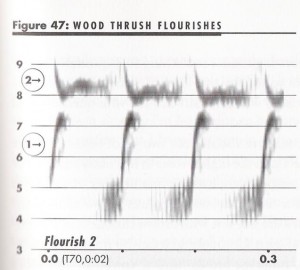

For the sheer beauty of song, you must read the discussion of thrushes. To describe their magical music, Kroodsma reminds us of how birds produce sound. With minor exception, birds produce sound in two voice boxes (syringes), located one each in the upper part of the left and right primary bronchi, just after they branch off the trachea. Thrushes can produce sound from either syrinx separately or sing different phrases from each syrinx at the same time, producing unbelievable harmony. (Kroodsma shows these sonograms, as well, using an expanded time scale and slowing the sound down to one tenth normal speed.)How the Wood Thrush brain can send impulses to the muscles of not only one but two syringes simultaneously, and create such beautiful and complex music, is absolutely amazing. You must see it and hear it to believe it.

This is a truly fascinating book. Only Kroodsma could have written it, and only after 30 some years of listening. It will forever change the way you listen to birds. – Eldon Greij

* * * * * * * * *

4b) The Living Bird

In the Field

Listen Up.

By Jack Connor

Around the globe, birds are always singing somewhere.

If you live east of the Rockies and south of the Canada border—in other words, anywhere within the range of the Northern Cardinal—I am willing to bet I can name a little blank on your birder’s resume. You might even be willing to admit it’s an embarrassing gap, a box you could have and should have checked off years ago in your own backyard. In fact, with a little determination and luck, you might have checked it off this morning. But you didn’t, did you? In fact, you have never gotten around to paying sufficient attention, have you?

You have never seen a female cardinal sing.

Welcome to the club! Cardinals nest in my yard every year, sometimes a couple of pairs. I’ve watched courtship feeding, nest-building, copulation, territorial disputes, incubation, and feeding of the young (by both sexes) in and out of the nest. I have also admired the cardinal’s loud and unmistakable song for as long as I have known it. His is generally the first song to reach me through the bedroom windows just before dawn most mornings from early March through midsummer: wheat-cheer-wheat-cheer . . . wheat-wheat-cheer-cheer-cheer! On those few mornings when I stop to notice, it’s a delightful way to start the day.

And yes, I know the books say the females sing too. I have often told people that. Clearing my throat, adopting my professorial voice, I have announced to one group of beginners or another, “Birdsong is primarily a male behavior, generally intended to intimidate males and to attract females. In a handful of species, however—Carolina Wren, Rose-breasted Grosbeak, and Northern Cardinal, for example—females also sing. This is something of a behavioral puzzle because . . . yadda, yadda, yadda.”

Luckily, no one has ever interrupted to ask, “But have you yourself ever actually witnessed any female cardinals singing with your own ears?”

Don’t tell my friends. I have missed it year after year—probably for the same reasons you have. We are visually oriented creatures, you and I. We believe and appreciate best what we can see. Birds originally attracted us because they are eye-catching and colorful, and a pleasure to watch. Only musically adept birders listen to birds as carefully as they look at them. And let’s admit it, you and I: we are not musically adept. For most birders like us, the calls and songs of birds fall a distant second to their visual appeal.

Therefore, you may be interested in the rehabilitation program I have designed and tested for birders just like us.

Step 1. Go to the bookstore and pick up two enlightening and engaging new books published nearly simultaneously, Don Stap’s Bird Song: A Natural History (Scribner, 2005) and Donald Kroodsma’s The Singing Life of Birds: The Art U Science of Listening to Birdsong (Houghton Mifflin, 2005). And yes, you need both.

Step 2. Before reading either, reach to the inside back cover of Kroodsma’s book, pluck out the CD of bird sounds you’ll find there, and slide it into the nearest player.

Step 3. Turn it on and listen. Play it the whole way through.

Step 4. Listen some more. Play it again, all the way to the end. Close your eyes and keep them closed. Tie a bandana around your eyes if you must. Give the knocks, chips, squeaks, whistles, shrieks, hoots, yodels, and rat-a-tat-tats your full attention. And no fair peeking at Kroodsma’s 30-page appendix where he identifies and analyzes each track in thorough detail. Save that for later. The CD itself lacks any verbal commentary, an arrangement that has several positive effects. Listening to more than an hour of pure bird sound (interrupted only by a brief track of Kroodsma’s baby daughter babbling) is more like the real-world experience of listening outdoors. Outdoors in the wild no narrator’s voice intones, “Next, here’s the song of the White-throated Sparrow.” Out in the real world bird sounds come direct to the ears, without interpretation.

You’ll recognize some of the sounds without help, of course—heck, even I recognized some of the songs and calls: American Robin, Black-capped Chickadee, Wood Thrush, Whip-poor-will, Blue Jay, Northern Cardinal.

Only an expert ear-birder could possibly identify them all (Bachman’s Sparrow? Three-wattled Bellbird? Sooty Shearwater?). But somewhere in that long series of sounds, perhaps even among the most familiar of sounds—oh, sweet Canada. . . chick-a-dee-dee-dee . . . peter-peter-peter . . . witchity-witchity-witch . . . tea-kettle-tea-kettle-tea . . . what-cheer-cheer-cheer-cheer—you might have a little epiphany. You might stop trying to identify this species or that and start thinking on a different level. What is this collection of noises all about? Wouldn’t even a Martian recognize that some kind of communication is going on here? And wouldn’t even a Martian want to know what is being said? These are Earthlings talking! The sounds of our fellow passengers on this planet bubble up around us every day of the year, but too often we ignore them. Once a year on the Christmas count we might go out in search of owl calls, but how many other days have you woken up early to go our in acoustic pursuit of birds? For a few, short weeks in spring we might use our ears again to identify migratory songbirds, then possibly once or twice in fall we might consciously listen for the call of a Bobolink or Dickcissel passing overhead. For the rest of the year, most of the sounds of birds pass by unnoticed, especially the sounds of the species we hear most regularly.

Step 5. Time to open Birdsong: A Natural History. Here, Don Stap, author of the equally wonderful A Parrot Without a Name, sketches and celebrates the study of the sounds of birds, from cave paintings in Lascaux, France, and the observations of Aristotle to the 130,000+ recordings currently archived in the Lab of Ornithology’s Macaulay Library. Best of all, he sketches the science by narrating several of the acoustic expeditions and investigations Donald Kroodsma has conducted over the past 10 years.

Kroodsma’s career-long dedication to the pursuit of bird sounds begin on the morning of May 5, 1968, as he listened to a Marsh Wren singing during his last year of college. It has continued for nearly four decades all across North America and down into the tropical forests of Central America and has made him now probably the most accomplished acoustic ornithologist in the world—which makes it especially satisfying that you can close the last page of Don Stap’s book and immediately . . .

Step 6. Read The Singing Life of Birds. Here you’ll need to slow down a little. It’s an easy book to skim, filled with anecdotes, puzzles, and Kroodsma’s contagious enthusiasm for the sounds of birds (“Although mothers play Mozart to babies in the womb, I think thrushes and wrens and sparrows and a more natural chorus would be at least as effective.”) But if you want to employ some of Kroodsma’s methodology you’ll need to study his approach and his thinking and also sharpen your brain for better listening. Kroodsma advocates counting sequences of songs and taking notes about individual differences and changes in sequences. He also makes a very good case for buying a microphone and parabolic reflector. You may not be ready for that step, but as long as you have a notepad, pen, and digital watch, his book will prepare you to . . .

Step 7. Go out the door yourself predawn, in pursuit of the morning chorus. If it’s too dark to see any bird and too early for any to be singing, you are right on time.

No, I didn’t hear the song of the female cardinal this spring, at least not consciously, despite several mornings of stumbling around and banging my shins on the backyard furniture. (Question for Kroodsma: are female cardinals discouraged by human observers skipping around on one leg while shouting curse words to the skies?) But I did hear several of the phenomena Stap and Kroodsma describe: repertoire bouts by dueling Northern Mockingbirds, dueting by

Carolina Wrens, song exchanges by neighboring cardinals.

So, my quest has been only partially successful so far. But that’s okay, because the most important step is the last one:

Step 8. Continue the chase. Maybe the cardinal will sing her song for me tomorrow—or maybe for you. Let’s pay better attention, you and I. Let’s listen more often to what we can hear.

“Always, somewhere [on the globe], it is dawn,” Kroodsma has written, “and always, somewhere, the birds are singing.”

* * * * * * * * *

4c) Midwest Book Review

Original web page here

The Singing Life of Birds: The Art and Science of Listening to Birdsong

Donald Kroodsma

Houghton Mifflin

ISBN: 0618405682 $28.00; xii + 482 pp.

by Thomas Fortenberry

“How do I hear with my eyes?” Donald Kroodsma asks, and yes he has an answer. The answer is the heart of The Singing Life of Birds. This amazing book documents in text, sonographs, and an accompanying CD collection, a vast range of birdsongs. Kroodsma, a professor emeritus at the University of Massachusetts, has studied birdsong for over 30 years and is recognized by all as a master in this field, or, in the words of the American Ornithologists’ Union, as “the reigning authority on the biology of avian vocal behavior.” Kroodsma has done it so long he professes, “As a bird sings, I see the rudiments of a sonogram form in my mind.”

The wonder of this book is its shared passion. Make no mistake, this man is a lover. A very thorough, serious scientist, Kroodsma could easily have buried his readers in the hundreds of pages of explorations, experiments, explanations, charts, graphs, and tables that make up this book. But he does not mar the mystery or attraction of his subject with a numbing rubble heap of facts. He has the rare gift of not just listening, but communicating. He shares his passion with us in such a way that we long to join him, long to stand beneath the trees and immerse our selves in the ebb and flow of birdsongs. In this way, Kroodsma has accomplished a very unique thing: interspecial translation. He transcends not just language barriers, but the boundaries between species. It’s not a literal translation, but it is intimate and accomplishes empathy, a shared emotional translation. This is an engaging and beautiful study, a work that, mirroring its subject in Mother Nature, becomes a work of art itself. This is why it is subtitled “The Art and Science of Listening to Birdsong.”

It has been said of Kroodsma that he has the mind of a scientist and the soul of a poet. I have to agree, though perhaps his poetry is birdsong rather than human speech. Nevertheless this is a joyous hymn to birds that touches on the sublime. “There’s this wonderful Zen parable,” Kroodsma says. “If you listen to the thrush and hear a thrush, you’ve not really heard the thrush. But if you listen to a thrush and hear a miracle, then you’ve heard the thrush.” He’s recorded these miracles and shared them with us all.

The Singing Life of Birds is a wonderful book. It is as in-depth a study of the subject as can be found, but it is also easy to read, easy to comprehend, and accessible to all, novice and expert alike. It tells us how to become an expert. It requires nothing more than opening our ears. Shakespeare sums it up, “The earth has music for those who listen.”

In the preface Kroodsma states “Somewhere, always, the sun is rising, and somewhere, always, the birds are singing.” This fact is also a clear philosophy and the best summation of Kroodsma’s outlook on life. In his world the sun is always shining and the birds are always singing. Thank God he’s invited us to join him on his journey.

* * * * * * * * *

4d) Wilson Journal of Ornithology

THE SINGING LIFE OF BIRDS: THE ART AND SCIENCE OF LISTENING TO BIRDSONG. By Donald Kroodsma, illustrated by Nancy Haver. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts, and New York, New York. 2005: 482 pp., CD of recordings. ISBN: 0618405682, $28 (cloth).

“Somewhere, always, the sun is shining, and somewhere, always, the birds are singing.” So begins Don Kroodsma’s celebration of birdsong, The Singing Life of Birds. On every page, Kroodsma reveals his passion for birds, his infatuation with birdsong, and his desire to unravel the mysteries of avian singing behavior. More than a celebration, the book is Kroodsma’s attempt to answer the “why” questions of birdsong. Why do some species learn their songs? Why are the songs of other species innate? Why do some species have dialects, whereby birds match the songs of their neighbors? Why would other species be unable to learn neighboring songs? Why do mockingbirds mimic? Why do females of some species sing? Kroodsma attempts to answer such questions with 30 different adventures—30 accounts of birds singing their stories—and shares three decades of recording and analyzing songs. Traveling widely across the Americas—from the eastern to the western U.S. and from Saskatchewan to Central and South America—often enlisting the aid of countess colleagues and students, Kroodsma takes us along on his exploits as he recounts his recording experiences.

The common thread running throughout the book is an emphasis on the combination of listening to (songs on the CD) and seeing (sonagrams) bird songs. It is the sight of sound that excites Don Kroodsma, and he infects the reader with his enthusiasm (“. . . I can’t imagine a world without sonagrams, as I can’t imagine listening without also seeing.”). Using sound spectrograms and the accompanying CD of bird songs, he considers how birds acquire their songs, what makes their songs unique, what functions songs serve, and “how the pieces of this singing continent fit together.”

Chapter 1 introduces readers to the elements of sonagrams: how to interpret the time-frequency displays of sonagrams; how to distinguish noisy, complex sounds from pure-toned, whistled sounds; how to recognize the rhythm and amplitude evident in sonagrams; and, how to learn to listen (“How do I hear with my eyes?”). Kroodsma also shares his personal beginnings and interest in birdsong in this chapter, crediting the Bewick’s Wren (Thryomanes bewickii) as the bird that first taught him how to listen. He ends the chapter by outlining the kinds of questions he asks—and attempts to answer—throughout the book. How, where, when, and from whom do birds acquire their singing vocabulary? What are the functions of different bird sounds? How do a bird’s life history features and its evolutionary background influence song? How do the brain, syrinx, and hormones control and influence birdsong?

As Kroodsma takes readers on his pre-dawn vigils, he reflects on the music of nature and the journeys on which birds have taken him. He bikes across Martha’s Vineyard, astonished to hear and record improbable sweetie-heys from Black-capped Chickadees (Poecile atricapillus) (across the continent, nearly all other chickadees sing hey-sweetie). He traipses across, canoes through, flies to, and crisscrosses, visits, and revisits Illinois, South Dakota, New York, North Carolina, Michigan, California, Colorado, Saskatchewan, Iowa, and Nebraska—all to identify “The Great Marsh Wren Divide” that distinguishes what are almost certainly two different species of Marsh Wren (Cisothorus palustris). Kroodsma spends an entire early-May night (20:10–05:04) following one male Whip-poor-will (Caprimulgus vociferus), and counts 20,898 tuck-whip-poor-WILLs—2,300 songs/hr and 40 songs/min in just under 9 hr. And then he asks, “Why so much song?” (Because the moon was full? Because the weather was warm? Because Whip-poor-wills had just returned from migration? Do high song rates reflect genetic superiority or good territories?) Relentlessly curious, always intrigued, Kroodsma is continually searching for answers.

Kroodsma’s enthusiasm is one of the most notable and enjoyable features of his book. I offer only a few examples: (1) “Hear the DNA of this flycatcher speak . . .”; (2) “I love the way song ‘G’ begins . . .”; (3) “There’s something universal in the quality of these sounds [of Sooty Shearwaters, Puffinus griceus], and it seems fitting that the birds themselves have the final comment about the sheer wonder and joy of birdsong.”; (4) “. . . I can’t help but . . . admir[e] how the black images of songs against the white paper reveal the magic in the singing bird.”; and, (5)“ . . . songs of some [Fox Sparrows, Passerela iliaca, are] so beautiful that they can bring tears to the eyes.”

Kroodsma shares many of his discoveries about birdsong with readers. For example, there are two birdsong vocabularies and two species (eastern and western) of Marsh Wrens, not just one. The songs of Eastern Phoebes (Sayornis phoebe) and Willow (Empidonax traillii) and Alder (E. alnorum) flycatchers are innate, not learned. Sedge Wrens (Cistothorus platensis) improvise (make up their songs) and they do not imitate (learn songs) from their neighbors as other wrens do—because Sedge Wrens are nomadic due to the unpredictability of their sedge-meadow breeding habitats. Song Sparrows (Melospiza melodia) that match and share songs with their neighbors keep their territories longer—and may live longer. A young Bewick’s Wren learns his father’s songs early in life, but in the following years, after occupying a territory of his own, he replaces his father’s songs by matching those of neighboring males. Kroodsma also lets us in on the fact that the meetcha song switch of a male Chestnut-sided Warbler (Dendroica pensylvanica) is turned “off” if he has a female, but it is turned “on” if he is without a female (males sing several meetcha songs, e.g., wheedle wheedle wheedle wheedle sweet sweet MEETCHA).

There are 68 figures, nearly all of which are sonagrams; these are flawless and impeccably prepared and presented. Some sonagrams are presented at an expanded time scale to show greater detail, and songs of these sonagrams can also be heard on the CD, but are played at a correspondingly slower pace. Figure captions offer straightforward explanations about how to interpret the notes and “read” the sonagrams; Kroodsma points out the intricate details and encourages readers to follow along on the CD—to hear, and see, birdsong at the same time. The CD (98 tracks, ~73 min) contains superlative recordings of more than 50 species—to aid readers in the interpretation of the sonagrams or for sheer listening enjoyment.

Appendix I (Bird Sounds on the Compact Disc) provides detailed, colorful descriptions of the bird sounds on the accompanying CD. Appendix II (Techniques) offers useful advice on how to listen to and record birdsong, on the recording equipment needed to do so, and on the software for making sonagrams. At the end of Appendix II, Kroodsma notes that “There’s no longer any mystique to what I have done all these years. Anyone can do this kind of stuff. And anyone should.” The Notes and Bibliography chapter provides a short section on recommended readings, an annotated list of readings for the key topics discussed in text, and a formal, extensive bibliography. A well-organized, all-inclusive index—referencing key topics, CD tracks, the locations of sonagrams in text, and the most important information for the key species discussed—completes the volume.

Cautious, meticulous, thoroughly prepared, objective, and determined to know, Kroodsma takes the reader, with lively, often stirring prose, on 30 fascinating journeys. No matter what your level of ornithological expertise, after reading this book you will have learned to listen to, and to look at, birdsong in a different way, and you will have broadened your understanding of avian singing behavior. As Kroodsma reminds us (quoting Shakespeare), “The earth has music for those who listen.” I highly recommend this book.—JAMES A. SEDGWICK, USGS Fort Collins Science Center, Fort Collins, Colorado; e-mail: jim_sedgwick@usgs.gov

* * * * * * * * *

4e) Journal of Field Ornithology

The Singing Life of Birds, the Art and Science of Listening to Birdsong.

D. E. Kroodsma. 2005. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, New York. CD and 482 pp. $28.00.

There is only one word to describe this book—superb! Written for the amateur ornithologist, naturalist, and others curious about their natural world, the book is about as far from a dry, academic accounting of bird song and singing than one can imagine. It reminded me of Henry Mitchell’s book “One Man’s Garden”—a sortie into a field by a master that also portrays how and why the master got into the field in the first place. Serendipity played a role in turning Don Kroodsma from a young chemist into a biologist during his late undergraduate years. Provided with a tape recorder, to fulfill a research requirement for a summer course at The University of Michigan Biological Station, he got hooked. He was hooked forever on bird song and that is just what he wants his readers to become—hooked on birdsong. Unlike Kroodsma’s indiscriminant enthusiasm for bird song recording, Henry Mitchell was slightly more reserved in his choice of candidates to become gardeners: “There is no need for every American to be lured into gardening. It does not suit some people, and they should not be cajoled into a world they have no sympathy with. Many people, after all, find their delight in stealing television sets; others like to make themselves anxious with usury and financial speculation; still others rejoice in a life of murder. None of these is very good material for a gardener.”

Singing Life should hook a lot of people as it is a very good read with a fine structure. Don combines pieces of his own biography with personal adventures in his quest to understand bird song. He must have taken incredibly detailed field notes for events several decades past are portrayed as though they happened last summer. The result is a readable adventure story as well as a discourse on how to listen to birds. How to listen to birds? Well, ‘with your ears of course’ you might say but, if this is your attitude, you miss one of the main points and one of the outstanding features of this book. You have not really listened to bird song until you come to realize that there are patterns, individuality, redundancy, and diversity in an individual bird’s song. A master teacher, Don uses a familiar example of singing, the American Robin, to introduce you to how to really listen, and remember, his patterning of song phrases, his unique use of song phrases, and his use of hissellys (a high-pitched, complex, series of songs placed at the end of the loud caroling phrases or sung in series at close range to females). The talents to listen and observe, capacities that naturalists expand over a lifetime, are shown over and over to lead to new discoveries and new questions to pursue about the function and evolution of bird song. Learning to really listen is an essential part of the adventures offered in this book.

Six chapters cover subjects that Don contributed major insights to: how songs develop, how songs vary from place to place, extremes of male song, she also sings, and the hour before dawn. I chuckled to myself over the “the hour before dawn” chapter title because this could just as well have been a subtitle for the entire book. Many depictions of field work on individual species began in the dark of night. So many, that it occurred to me that Don, like Henry Mitchell, might include some people that sleep past 6AM in the “non-gardener” category! Nonetheless, these chapters focus on individual species, many of which do have predawn songs and singing styles that differ later on in the morning, and it was a treat for me to learn of them (ahem). But at least 33 species are described in detail (16 more in less detail) and illustrate the focus of each chapter. One of the features I really enjoyed was the CD accompanying the book. I could listen to the sounds depicted in the text which was richly illustrated with spectrograms and descriptions of the complexity of bird songs, many of which were slowed so that my ears could follow the ups and downs of frequency and see the way trills and buzzes look when separated into their time and frequency components. Finally, if you do become hooked on recording bird song, there is an appendix covering techniques, microphones, tape recorders, and the like. Another appendix describes the contents of each track on the CD, so that one can follow along listening to the CD without the need to skip between reading the text and then turning on the CD player.

The writing was more than meets the eye in another way as exemplified in this quote from the blue jay account: “Yes, I’m hooked on these songbirds without a song. I’m convinced there’s something deep and rich here, that spending time studying the pairs at a few nests and listening to these jays awake will provide a window on their minds. It is to understand their minds, after all, that is my goal, as I use their sounds only as a tool to that end.” Don is clearly hooked on the charm of the philosopher Charles Hartshorne (“Born to Sing”) and the cognitive ethology school of Donald Griffin and Peter Marler. We can only hope that Don will pursue answers to many of the questions that arise from his early morning eavesdropping. I hope he writes about it in a magazine article format, if not another book eventually. We will all benefit!

Eugene S. Morton, Hemlock Hill Field Station, 22318 Teepleville Flats Road, Cambridge Springs, PA 16403

* * * * * * * * *

4f) Bird Watcher’s Digest

Spring 2006

Review by Diane Porter

http://www.birdwatchersdigest.com/

THE SINGING LIFE OF BIRDS—A PERSONAL REVIEW

by Diane Porter

The Singing Life of Birds

Donald Kroodsma. Illustrated by Nancy Haver. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2005. ISBN: 0618405682, 482 pages, 7” x 9”, $28, hardback, with CD recordings of birdsongs.

Donald Kroodsma has devoted his professional life to studying birdsong. Professor emeritus at the University of Massachusetts, he is an authority on the vocalizations of birds. His book, The Singing Life of Birds, is that rare marvel, a work by a scientist about science that everyone, including non-scientists, can understand. Nothing I’ve ever read has had more impact on how I experience birds and their songs.

Singing Life takes us far beyond mere identification and listing, into a realm where we begin to enter the bird’s world and get a sense of what the bird is doing. The author lets us in on the process that his scientific mind goes through as he poses questions about each bird and seeks to answer them by paying active attention to and rigorously analyzing its songs. His inquiries range over how the bird interacts with its neighbors, the “rules” which govern its songs, how it acquires its repertoire, and how each species’ songs come out of its evolutionary history.

Writing in the first person, Kroodsma takes us with him on his journeys of exploration with 33 species. Some are stories of his own research. Others report on the work of ornithologists with whom he has collaborated. In each episode, he shares with us what has been discovered by using bird song as a window on the life of the bird. At the same time we’re learning about bioacoustics, the recording and study of animal sounds. We also see that the methods he uses are not difficult, and the equipment for analyzing bird sounds is readily available. Reading his book, we realize that we can do this too!

The book begins by intr oducing the sonagram, a picture of a bird’s song that displays the pitch, intensity, and rhythm. The sonagram is crucial to the study of bird songs. Although most birds’ songs are within the range of human hearing, it’s impossible for us to hear everything. There are too many details, too quickly executed, for our human brains to register all that is going on. But with the help of a sonagram, the song is revealed. “It is with my eyes that I hear,” declares the author. Throughout the book, wherever a song is mentioned, we see the sonagram on the page. Many of these sonagrams would be worthy of framing simply for their calligraphic beauty, even if they were not the keys to reveal the complexity of bird vocalizations.

oducing the sonagram, a picture of a bird’s song that displays the pitch, intensity, and rhythm. The sonagram is crucial to the study of bird songs. Although most birds’ songs are within the range of human hearing, it’s impossible for us to hear everything. There are too many details, too quickly executed, for our human brains to register all that is going on. But with the help of a sonagram, the song is revealed. “It is with my eyes that I hear,” declares the author. Throughout the book, wherever a song is mentioned, we see the sonagram on the page. Many of these sonagrams would be worthy of framing simply for their calligraphic beauty, even if they were not the keys to reveal the complexity of bird vocalizations.

The equipment

An appendix describes the needed recording equipment and software. Kroodsma suggests a variety of microphones, head phones, and recorders. He describes how to start for very little money but warns that bird recording is addictive, and once a person gets hooked, equipment upgrades are likely to follow. One of the great tips I found in the appendix was about Raven Lite, a $25 software program I could download from the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology (http://www.birds.cornell.edu/brp/RavenLite/RavenLite.html).

This marvelous program turns recorded bird songs into sonagrams, in elegant black and white or in wild colors that reveal the relative loudness of each frequency. Raven Lite lets me stretch out any snippet of sound to fill my computer screen, so that I can see delicate details of a bluebird’s song, count off the frequency of a chipping sparrow’s trill, and confirm that I really did hear that soft introductory note of the whip-poor-will’s chant. With a few keystrokes I can even filter out most traffic noise and then listen to my birds sing as if we were in a pristine wilderness.

What a revelation it was, those first mornings that I went out and aimed my microphone at every song I heard, or simply stood still and recorded everything at once. When I fed my recordings into the computer and played them while watching their sonagrams, I saw the shapes of the birds’ songs jump out at me. I quickly learned to recognize by sight which birds were on a recording. Here was the jagged mountain range of the common yellowthroat’s wichity-wichity-wichity. Those square, dark blocks of sound meant eastern meadowlark.

And just as binoculars magnify sight, Raven can slow sounds down, revealing structures that unaided human ears would not be able to distinguish. At ½, or 1/10, or even slower speeds, with the help of sonagrams, I felt I was beginning to perceive the details of what each bird was singing.

The two voices of a songbird

Kroodsma also investigates how the bird physically produces its songs. I’d heard t hat songbirds have two voice boxes, and I’ve always wondered what they were for. I found the answer in the sonagram of a wood thrush in Singing Life. The wood thrush sings a two-part song. First comes what Kroodsma calls the prelude—three or four single notes of unworldly beauty. Then follows a flute-like trill or flourish. In the sonagram of the flourish, you can clearly see that the bird is producing two different notes simultaneously, an effect that would be impossible to generate with a single voice box. The thrush is singing harmony with himself. (In the sonagram, the output of the two voice boxes are labeled “1” and “2.”)

hat songbirds have two voice boxes, and I’ve always wondered what they were for. I found the answer in the sonagram of a wood thrush in Singing Life. The wood thrush sings a two-part song. First comes what Kroodsma calls the prelude—three or four single notes of unworldly beauty. Then follows a flute-like trill or flourish. In the sonagram of the flourish, you can clearly see that the bird is producing two different notes simultaneously, an effect that would be impossible to generate with a single voice box. The thrush is singing harmony with himself. (In the sonagram, the output of the two voice boxes are labeled “1” and “2.”)

The CD inside the back cover has the sounds of all the sonagrams shown in the book. For the wood thrush, in addition to the normal speed, Kroodsma has also slowed down the prelude to ¼ speed, a rate at which we can better appreciate the introductory whistled notes. Then he slows the flourish down even more, so that our ears can distinguish its components, which emerge at 1/10 speed as a series of bell-like tones.

The CD inside the back cover has the sounds of all the sonagrams shown in the book. For the wood thrush, in addition to the normal speed, Kroodsma has also slowed down the prelude to ¼ speed, a rate at which we can better appreciate the introductory whistled notes. Then he slows the flourish down even more, so that our ears can distinguish its components, which emerge at 1/10 speed as a series of bell-like tones.

Next, using the stereo capability of Raven, Kroodsma separates the sounds of those two simultaneous voices in the flourish. To emphasize the distinction between them, he makes a version of the flourish with the sound of just one voice and sends it to the left channel of the recording. He makes another version for the other voice and sends it to the right channel. To complete the exercise, he makes a combined version, with both voices playing at once in stereo.

Through headphones, while following along on the sonagrams, the reader can listen to each voice separately and then the haunting harmony they create together. What composer, I wondered, has created anything so wonderful? What musician has mastered his instrument better than this bird, who has so perfectly coordinated his two voices? After I listened myself, I carried the CD and a player around for days and made all my friends listen to that track, just for the pleasure of watching their jaws drop in astonishment.

But Kroodsma was not finished investigating the songs of his wood thrush. After recording and analyzing a long session of the bird’s singing, Kroodsma identified six distinct preludes and 13 flourishes. The bird repeated each prelude and each flourish in the same way each time he sang it, but he put the two parts together in different combinations, for a repertoire of 22 recognizable songs. He never sang the same complete song twice in succession. Furthermore, he never sang the same prelude, nor the same flourish twice in consecutive songs. Some of the preludes were similar to one another in pitch, and the bird kept those separated as well, so that each song began on a much higher or much lower pitch than the song that came before. It was as if the wood thrush sang according to rules designed to create contrast between successive songs.

And yet his singing was never predictable, because he did not run through his songs in a set order. He varied his sequences endlessly, always abiding by his wood thrush rules. The effect was dramatic, exquisite both to the ears and to the analytical mind.

Invitation to explore birdsongs

Each bird species has its own rules for how songs are constructed and chosen. Any many individual birds have their own variations on their species’ rules. Discovering what those rules are is powerful way to understand birds. Singing Life gives one the sense of how new and exciting this subject is. In chapter after chapter, Kroodsma cajoles his readers to join in the study of bird songs. At the conclusion of each story, Kroodsma outlines questions for others to investigate and follow up on.

How many songs does a sage thrasher really know? How do neighboring tufted titmice agree on which of their four songs they will all sing at once? Why do red-eyed vireos sing all day long, and does it have anything to do with which male is the father of the babies in the nest? Here are questions for the grad student seeking a topic for a thesis. Here are worthy projects for birders who want to go beyond the superficial. Here are suggestions for how to have extraordinary fun in one’s own back yard.

They are questions about birdsongs, but they are really questions about the mind of the bird. “It is to understand their minds, after all, that is my goal,” writes Kroodsma. “I use their sounds only as a tool to that end.”

How this book has affected me

King Solomon, according to medieval legend, possessed a magical ring that allowed him to understand the language of animals and birds. I’ve always wanted that ring. It’s a dangerous desire, however, because wishful anthropomorphizing can begin to dominate over scientific observation. Kroodsma’s book showed me a way to study the mind of the bird, to reach for that ring while still staying grounded in the scientific method.

Kroodsma always asks the question of how its singing behavior helps a bird to compete in the evolutionary contest for who is going to leave babies in the next generation. It’s generally accepted that birds’ songs serve two main functions—competition for territory, and a means to advertise for and hold a mate. Kroodsma theorizes that sexual attraction may be the most important one.

Although some female birds also sing, it is males who contribute most of the birdsongs we enjoy on a spring morning. But it is the female bird, Kroodsma argues, who is the architect of male song. Females choose which males they will mate with. In the process of natural selection, the female bird does a lot of the selecting. Why does the wood thrush sing his heart-rendingly beautiful song? Because the female is listening. Because, over the generations, by choosing her mates, she has shaped his song and even the vocal apparatus by which he sings. Aesthetic taste of the female wood thrush, which has evolved over the long history of the species, coincides with our human sense of beauty. A remarkable congruence, to be sure.

Since reading this book. I hear with new ears. I’ve hooked up headphones to a small microphone mounted outside my bedroom window. On the coldest night of the Iowa winter, I put on my headset and listen for the sounds of the outdoors. At first I hear only a frozen leaf  clattering on the icy-covered ground. Then, in the distance, a car passes, and off in the woods a barred owl stirs, says hoo-awww” Another barred owl answers, higher pitched, with a tremulous hoo-aww-w-w-w. I know this second voice belongs to the female. In his episode on the barred owl, Kroodsma describes how he discovered that the female barred owl, and only the female, hoots with vibrato. Thanks, Kroodsma, for showing that to me. I’ve heard both members of the pair this night, and smiling I go back to sleep.

clattering on the icy-covered ground. Then, in the distance, a car passes, and off in the woods a barred owl stirs, says hoo-awww” Another barred owl answers, higher pitched, with a tremulous hoo-aww-w-w-w. I know this second voice belongs to the female. In his episode on the barred owl, Kroodsma describes how he discovered that the female barred owl, and only the female, hoots with vibrato. Thanks, Kroodsma, for showing that to me. I’ve heard both members of the pair this night, and smiling I go back to sleep.

Going outside on a winter morn ing, I hear a tufted titmouse singing. It’s early February, and already he’s at it. Peer, peer, peer, he sings. From a distance, perhaps three oak trees away, I hear a response, a fainter version of the same song. Strange how all these years I have listened to one titmouse at a time and never paid much heed to the other parts of the conversation. Now I want to hear more of these titmouse exchanges, compare my notes to what Kroodsma found when he perched on his rooftop in the pre-dawn darkness with microphones aimed at the tufted titmice in his yard and neighborhood.

ing, I hear a tufted titmouse singing. It’s early February, and already he’s at it. Peer, peer, peer, he sings. From a distance, perhaps three oak trees away, I hear a response, a fainter version of the same song. Strange how all these years I have listened to one titmouse at a time and never paid much heed to the other parts of the conversation. Now I want to hear more of these titmouse exchanges, compare my notes to what Kroodsma found when he perched on his rooftop in the pre-dawn darkness with microphones aimed at the tufted titmice in his yard and neighborhood.

By the time I’d read Kroodsma’s book last year, the peak season of bird song had passed. This year, however, I’m ready with microphone, recorder, and headphones, and I can hardly wait for spring. When dawn breaks on an April morning, I’ll be on the path between a certain plum thicket and a willow clump, where last year two Bell’s vireos sang for months on end.

I want to find out whether they sing just alike, or if I can recognize each individually by its songs. I want to listen with a new level of attention to what they are communicating. Are they reacting and responding to each other? Do their songs change depending on where they are in their nesting cycle, as I’ve read? Whatever they sing, I’ll be recording the exchanges, pondering what it all means, using song to try to understand the mind of the bird.

* * * * * * * * *

4g) Scientific American

May 2005

How to Listen to Birds. An expert shares his secrets.

Review: The Singing Life of Birds. The Art and Science of Listening to Birdsong. By Donald Kroodsma, Houghton Mifflin, 2005 ($28, includes compact disc)

by Bernd Heinrich

Just as the colors and patterns of the feathers that birds wear show tremendous variation, so, too, do the songs that they broadcast–but much more so. Songs may be absent, or they may range from a few simple genetically encoded notes endlessly repeated, to virtuosos of variety resulting from copying and learning, and even to seemingly endless improvisation. In The Singing Life of Birds, Donald E. Kroodsma, an emeritus professor of biology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, celebrates the diversity through carefully chosen examples, one for each of the 30 years that he has studied birdsong.

The book is best described by its subtitle, The Art and Science of Listening to Birdsong. Kroodsma shares his secrets–solid, practical advice on how to record bird sounds and how to “see” the sounds in sonagrams, visual representations of the recordings of songs. A compact disc that accompanies the text aids readers in this task. He concludes: “There’s no longer any mystique to what I have done all these years. Anyone can do this kind of stuff. And anyone should.”

His infatuation started with a single male Bewick’s wren in his backyard in Oregon. Kroodsma discovered that this one wren sang 16 different songs, and in any singing bout it poured forth 40 to 50 renditions of one of them before switching to another, and then to another, and on and on. Meanwhile neighboring wrens hearing the song replied with the same one, while distant males sang other songs. Why?

The proximal answers to why birds sing and what they sing run from the trivial to the fascinating: they enjoy it, they are primed by hormones that activate neuronal pathways, they respond to neighbors. But the ultimate, evolutionary question of why they sing and what they sing can be answered only by the comparative study of many species.

Sometimes the anomalies provide a clue. For example, most individual wrens of different species learn many songs, and neighboring birds have similar songs–that is, they have dialects. The sedge wren of North America is an exception, however. Unlike other wrens and the sedge wrens of Central and South America, it has lost the ability to learn songs; it can only improvise on songs that are inscribed on its DNA. It is therefore unable to “match” the songs of its neighbors, and no dialects are found.

So what is different about the North American sedge wrens in respect to other wrens? They are nomads that live in unpredictable habitat–meadows that can quickly dry up. As a consequence, these birds can never predict who their neighbors will be from one season to the next; hence, learning songs as youngsters for later use in song matching is pointless. Contrast this to the bellbird, a long-lived tropical bird in which individuals come to know one another well. These birds listen to one another all year long and learn the changes in others’ songs throughout life. The young birds learn the latest of these variations, and the dialect of the population changes from year to year.

Kroodsma takes us repeatedly into the field, into the birds’ world. He shares an all-night vigil with a whip-poor-will, tallying 20,898 identical repetitions of its one song for the entire night. He describes a brown thrasher that in one two-hour session sang 4,654 songs, 1,800 of them different (many borrowed from neighbors of other species). We enter the mind of the researcher as he tries to penetrate the mind of the bird.

As much as we humans may enjoy the spectacle of birds flaunting their gaudy garb to the accompaniment of vocalizations and dancelike antics, the show is meant primarily to attract females. It is about sex–about who will be the father of the female’s chicks. The males presumably enjoy putting on their show, but whatever else it may do for them (such as serving as a territorial marker), it is the females who have shaped the performance by their tastes and preferences, and these are as various as the 10,000 or so species of birds.

Kroodsma emphasizes that we know little about why one or another bird has a specific repertoire. Yet despite the dazzling variety, it appears to me that all birdsongs have general requirements and constraints, and I believe that these shared characteristics may in themselves shed some light on the enigma. The primary requirement of a species’ display song is that it must stand out from environmental noise–that is, it must carry–and it must be distinct from competing voices on the stage. Once females reward a specific song type with mating, then success breeds success, and whatever it is that attracts, the male that has more of it enjoys a huge advantage.

But singing is not cheap: the performers are conspicuous to predators, and the displays are so costly in time and energy that the performers may appear to handicap themselves. I doubt, however, that it is the flaunting of handicap as such that attracts the females (“I am so strong and healthy that I have energy to waste on singing”). The singer must cater to the females’ taste. As in our own fashions of clothing and music, there is not necessarily rhyme or reason in the specifically chosen attribute, except the most important one–it works.

Konrad Lorenz reputedly said that birdsong is “more beautiful than necessary.” It seems to me that it is just as likely that the flamboyant displays of song and dance, of feathers and, in the bowerbirds, of decorated love shacks are indeed necessary, because females compare, and they are picky. Arbitrary though their criteria of choice may be, it is significant that we humans also find many of the same displays beautiful. –Bernd Heinrich is professor emeritus at the University of Vermont and author of many popular books on science. Among the most recent are The Geese of Beaver Bog, Winter World and Mind of the Raven.

* * * * * * * * *

4h) Birdchat.

4/11/2005

By Laura Erickson, Duluth, MN; Producer, “For the Birds” radio program

I’m in the middle of one of the very best bird books I’ve ever read: The Singing Life of Birds by Donald Kroodsma. It’s designed and laid out something like a textbook but  reads like a cross between poetry and a mystery novel, as we follow Don questioning how songbirds learn their songs. We follow his quest for answers as he learns that most songbirds learn their songs–some from their fathers and immediate neighbors during their nesting/fledging stages, some after they’ve moved on to their own territories farther afield–and that most sub-oscine passerine songs are genetic and unalterable. Then Don goes into an exploration of why there are exceptions to both rules. He delves into the complexities of what we know about bird song and dialects (much thanks to his own research), and explains in a thorough and rich way his own techniques for analyzing bird song, managing to preserve and even enhance our appreciation of the beauty and magic of bird song even as we learn to appreciate how its scientific analysis contributes to evolutionary biology and natural history. There are also wonderful anecdotes, like one with Don bringing a brood of Sedge Wren nestlings onboard airplanes and tenderly feeding them in the bathroom, needing to verify in a controlled captive setting what he first spent years documenting in the field.

reads like a cross between poetry and a mystery novel, as we follow Don questioning how songbirds learn their songs. We follow his quest for answers as he learns that most songbirds learn their songs–some from their fathers and immediate neighbors during their nesting/fledging stages, some after they’ve moved on to their own territories farther afield–and that most sub-oscine passerine songs are genetic and unalterable. Then Don goes into an exploration of why there are exceptions to both rules. He delves into the complexities of what we know about bird song and dialects (much thanks to his own research), and explains in a thorough and rich way his own techniques for analyzing bird song, managing to preserve and even enhance our appreciation of the beauty and magic of bird song even as we learn to appreciate how its scientific analysis contributes to evolutionary biology and natural history. There are also wonderful anecdotes, like one with Don bringing a brood of Sedge Wren nestlings onboard airplanes and tenderly feeding them in the bathroom, needing to verify in a controlled captive setting what he first spent years documenting in the field.

I’ve been passionately interested in bird song since I started birding and searched out every singer of every song I heard, and then took ornithology classes and started reading scientific papers about the origins of bird song. I’ve taken the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology’s fantastic field recording course, where Don Kroodsma gave one lecture and accompanied us in the field one day–that was one of the most interesting and valuable weeks of my life. So I was predisposed to love this book. But the writing is so engaging, the topic presented in such a thorough yet riveting way, that I think anyone with a mind and ears will find the book equally fascinating and valuable.

* * * * * * * * *

4i) The Bird Observer

The New England Birding Journal; See http://massbird.org/birdobserver/

The Hills are Alive with the Sound of Thrashers, Titmice, and Robins (i.e., Music)

by Mark Lynch

Excerpts:

” . . . Dr. Kroodsma is unapologetically passionate about birdsong. I have only seen this kind of uncurbed enthusiasm expressed by connoisseurs of Mozart symphonies and expensive fine wines. I have watched Don listen to a recording of a birdsong–his own recording at that. He breaks into a smile of sheer pleasure and wonder. It is the very picture of someone continually thinking: Wow!” And then the torrent of questions starts . . .

In The Singing Life of Birds, Kroodsma gives example after example of how unique and complex each INDIVIDUAL birdÕs song is. Reading this book is nothing less than revelatory and even mind-blowing. Shortly after starting this book, readers will feel that they have never actually listened to a birdsong before. It will seem that a garrulous and fascinating conversation has been going on all around us, and we have just never bothered to listen to it with a sufficiently critical ear. . . .

It is this seamless mix of passion and scientific dedication that makes The Singing Life of Birds one of the best books I have read to explain how real science gets done. . . .

The Singing Life of Birds is a groundbreaking book, a classic that will forever alter your experience of the natural world.”

* * * * * * * * *

4j) Critics’ Choice

Kroodsma, Donald E. The singing life of birds: the art and science of listening to birdsong. Houghton Mifflin , 2005. 482p bibl index CD ISBN 0-618-40568-2, $28.00 . Outstanding Title! Reviewed in 2005oct CHOICE.

Kroodsma (emer., Univ. of Massachusetts), a leading ornithologist in the study of birdsong, has skillfully combined a basic textbook with a highly readable account of his own extensive studies. He is one of those rare scientists who can translate his discipline for lay readers without sacrificing basic science. He seamlessly describes the complexities of various forms of birdsong using sonograms as his basic tool. Never has this reviewer read a clearer explanation of how sonograms are used and interpreted. Students should find this book inspiring, much in the tradition of Niko Tinbergen’s accounts of his various nature-based behavioral studies. Kroodsma uses six chapters and over 30 bird species to take readers on a journey through the realm of birdsong. The examples are concise and clear, and Kroodsma does not hold back from controversy, as with his contention that the marsh wren should be divided into several species on the basis of vocalizations. He shows that the assumption that sub-oscine birds do not learn their songs is wrong, at least for tropical cotingas. This very valuable book has three appendixes (including a primer on techniques) and comes with a CD containing all the vocalizations described in the text. Summing Up: Highly recommended. Lower-level undergraduates through graduate students; general readers. — J. C. Kricher, Wheaton College (MA)

* * * * * * * * *

4k) Publisher’s Weekly, Boxed Review

2/21/2005

THE SINGING LIFE OF BIRDS: The Art and Science of Listening to Birdsong

Donald E. Kroodsma. Houghton Mifflin, $28 (496p) ISBN 0-618-40568-2

Kroodsma, professor emeritus at the University of Massachusetts, shares what he’s learned from more than three decades of recording and analyzing the songs of birds in this intriguing, instructional book. Using “sonagrams” (also known as sound spectrograms, they plot a sound’s frequency over time), he illustrates the songs of 30 birds, from the familiar American robin to the exotic three-wattled bellbird of Costa Rica. He considers how birds acquire their songs (some species learn them; others have their tunes “encoded somehow in the nucleotide sequences of the DNA”), what makes the songs unique, what functions they serve, and how they’ve evolved. No two species sound alike, of course, but groups of birds within each species have their own dialects, and individual birds have their own repertoires as well. A CD of the bird songs discussed is included, as are descriptions of the recording equipment Kroodsma used and explanations on how to make similar recordings and “sonagrams.” Kroodsma is a warm, encouraging guide to the world of birdsong, and his enthusiasm is contagious. Illus. Agent, Russ Galen. (Apr.)

* * * * * * * * *

4m) Library Journal, *Starred Review*

3/15/2005

*Kroodsma, Donald E. The Singing Life of Birds: The Art and Science of Listening to Birdsong. Houghton. Apr. 2005. c.496p. illus. bibliog. index. ISBN 0-618-40568-2. $28 with CD. NAT HIST

Anyone who wonders why birds sing, if their songs are learned or inherited, why mockingbirds sing at night, or why some species mimic will find engaging answers in this authoritative and entertaining book on bird vocalizations. Kroodsma (biology, Univ. of Massachusetts) has studied birdsong for over 30 years; here he discusses how songs develop, different bird dialects, extremes of male song, songs in the hour before dawn, and even avian species whose females also sing. His text is augmented by drawings and song graphs (sonograms), the latter diagramming what is heard on the accompanying high-quality CD, which features 98 tracks and the virtue of no narration. A 36-page appendix explains each track, while another appendix details equipment and techniques for recording birds. Highly recommended. . . . –Henry T. Armistead, Free Lib. of Philadelphia

* * * * * * * * *

4n) Birdwatching.com

See the original post by Diane Porter here