From September of 1968, when I entered graduate school, to the stroke of midnight on December 31, 2003, I was “an academic,” intently pursuing the science of birdsong. As a graduate student earning my Ph. D., and then as a professor, my efforts were focused largely on communicating with other professionals like myself, and I summarize those scholarly activities here, in three sections.

Research questions

Academic resume

Professional edited books

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Research questions

I love asking a question and then pursuing the answer. That’s basically what research is, and it can be pursued by any inquisitive naturalist. Often I ask the question of a bird in my backyard, but sometimes the question requires travel to a distant land.

What follows are ten examples of the kinds of questions I’ve asked over the years and the answers that I’ve obtained. The examples I choose are from publications in ornithological journals, the entire articles of which are available on line (at https://sora.unm.edu/node) should anyone choose to read in more detail. Just enter “Kroodsma” in the author box and the name of the species in the title box.

1) Spotted towhees (1971)

2) Rock wren (1975)

3) Brown thrasher (1977)

4) Winter wren (1980)

5) Alder flycatcher and willow flycatcher (1984)

6) Marsh wren (1989)

7) Eastern towhee (1994)

8) Black-capped chickadee (1999)

9) Sedge wren (1999)

10) Three-wattled wellbird (2013) winner of Edwards Prize, best paper in Wilson Journal of Ornithology during 2013.

1) Spotted towhees (1971)

1971. Kroodsma, D. E. Song variations and singing behavior in the Rufous-sided Towhee, Pipilo erythrophthalmus oregonus. Condor 73:303-308. (You could read the original research article  here: Spotted Towhee–1971 Condor)

here: Spotted Towhee–1971 Condor)

Here is my first professional publication, my entry into the ornithological community. As a graduate student, I had been listening to spotted towhees (rufous-sided towhees at that time) on the William L. Finley National Wildlife Refuge in the Willamette Valley of Oregon, and I began to wonder. How many different songs does a male have? Do neighboring males have similar songs, suggesting that they’ve learned them from each other? If so, by recording males over a larger area can I discover where and when and from whom a young male learns his songs?

Answering these questions required extensive recordings of selected birds, but before long I had my answers. Each male sang seven to nine different songs, most of them shared with immediate neighbors. Walking away from a central neighborhood, I found that the songs changed rapidly over distance. I next verified that the males remain on their territories from year to year. Knowing that young birds disperse from home before settling on their own life-long territory, I could conclude that a young male leaves his father’s territory to find his own where he learns his songs from the males who will become his immediate neighbors.

2) Rock wren (1975)

1975. Kroodsma, D. E. Song patterning in the Rock Wren. Condor 77:294-303. (You could read the original research article here: Rock Wren–1975 Condor)

A male rock wren sings endlessly, song after song different from the one before, but in a detectable alternating pattern, such as A B A B A B, but then he introduces other songs. What’s he up to?

Three males at Oregon’s Malheur National Wildlife Refuge provided most of the answers. Each male had a considerable song vocabulary, and I recorded 69, 85, and 119 different songs from these three males. A male would sing a given song three to four times in a burst of 10-15 songs, alternating them in a sequence such as A B C B D C B D E F D E F G E H G E H G E H G I . . . (+ 44 songs) . . . X B Y B X B C B C B C . . . He’d sing in “packages,” working with a few different songs in one package, then going on to others, eventually returning to packages already delivered, such as with songs B and C above.

Even with this large repertoire of songs, males often answered each other with similar songs; rock wrens at more distant locations used different songs, revealing that males learn at least some songs in the local dialect.

3) Brown thrasher (1977).

1977. Kroodsma, D. E., and L. D. Parker. Vocal virtuosity in the Brown Thrasher. Auk 94:783-785.

(You could read the original research article here: Brown Thrasher–1977 Auk)

How can one not wonder what is on the singing mind of a brown thrasher? I couldn’t.

So one fine May morning I found my singing thrasher and stood beneath him while recording  113 minutes of his non-stop singing. Thrashers tend to sing in couplets, with our mnemonics such as good morning good morning, thrasher thrasher, spring’s here spring’s here, and I recorded 4654 of those couplets. After making sonograms of them all, we (my mother-in-law and I) took every 100th couplet, and searched for other examples of those 46 throughout the entire sample of 4654. It took a lot of looking!

113 minutes of his non-stop singing. Thrashers tend to sing in couplets, with our mnemonics such as good morning good morning, thrasher thrasher, spring’s here spring’s here, and I recorded 4654 of those couplets. After making sonograms of them all, we (my mother-in-law and I) took every 100th couplet, and searched for other examples of those 46 throughout the entire sample of 4654. It took a lot of looking!

Those couplets recurred an average of 2.6 or a median of 2 times. Dividing those numbers into 4654 gives an estimate of 1805 and 2327 different songs that the male sang during those 113 minutes. Wow! Those numbers remain a record for birdsong repertoires.

Even more intriguing, 20 of the couplets never occurred again. He never repeated them. It’s possible that a thrasher has an immense, stable repertoire of different songs and eventually we’d find repeats, but my hunch is that he can improvise as he sings, delivering totally novel songs that he’ll never sing again. The size of his song repertoire is thus, well, infinite.

4) Winter wren (1980)

1980. Kroodsma, D. E. Winter wren singing behavior: a pinnacle of song complexity. Condor 82:356-365. (You could read the original research article here: Winter wren–1980 Condor)

As a graduate student, while walking forests in the Pacific Northwest, I became mesmerized by  the long, intricate songs of the winter wren (now called the Pacific wren). Moving to New York in 1972, I found an altogether different winter wren. What gives? I needed answers.

the long, intricate songs of the winter wren (now called the Pacific wren). Moving to New York in 1972, I found an altogether different winter wren. What gives? I needed answers.

I learned that eastern males had limited song repertoires, with each male typically singing only two different songs. A male would sing one of his songs several times (up to 40 or so) before switching to the other. Western males were far more impressive; each male had about ten different song beginnings, and perhaps he’d sing 50 or more songs in a row with the same beginnings. But the songs could end in a seemingly infinite number of ways, depending on the mood (excited or not) of the bird at the time.

The quality of the songs was entirely different, too. Eastern songs were more pleasing to my ears, given that my ears could better appreciate the tonal (musical) notes that were delivered far more slowly than the fast-paced notes that raced through time and frequency in the songs of western birds. (But these wrens all clearly hear details that I can’t, as in both East and West, neighboring birds shared similar songs, indicating that they learned the details of their songs from each other.)

So different were these eastern and western birds that I found it hard to believe they were the same species. Well, they weren’t, or so concluded the American Ornithologists’ Union 29 years later, in 2009. These two birds are now the Pacific wren in the West, the winter wren in the East.

5) Alder flycatcher and willow flycatcher (1984)

1984. Kroodsma, D. E. Songs of the Alder Flycatcher (Empidonax alnorum) and Willow Flycatcher (Empidonax traillii) are innate. Auk 101:13-24. (You could read the original research article here: Alder-Willow Flycatcher–1984 Auk)

Songbirds learn their songs, it is routinely said. That means that a young bird (usually the male) must listen to accomplished adults of his species and learn the appropriate songs. As a result, local dialects often occur, because young males remain to breed (and sing) where they learned their songs.

must listen to accomplished adults of his species and learn the appropriate songs. As a result, local dialects often occur, because young males remain to breed (and sing) where they learned their songs.

But what about those other passerines? The Order Passeriformes consists of two groups, the song-learning songbirds and, well, those other birds, flycatchers and the like, largely centered in Central and South America. How do they acquire their songs?

Various hints suggested that no learning was involved, but I needed more certainty. So I raised baby alder and willow flycatchers, two look-alike “sibling species” so closely related and similar in appearance that they can be reliably distinguished only by song.

In all of my attempts to trick these birds into singing nonsense or the song of the other species, I failed. Under the same circumstances, songbirds would have been entirely confused.

In all of my attempts to trick these birds into singing nonsense or the song of the other species, I failed. Under the same circumstances, songbirds would have been entirely confused.

The songs of flycatchers are somehow encoded directly into the genetic material, so that each bird upon hatching knows exactly what it is to sing without any other exposure or tutoring from adults. Knowing that the songs are innate is important, so that, when surveying flycatchers and their (suboscine) relatives in the frontiers of the Tropics, the field biologist can reliably use songs to identify genetically different populations. As a result, many species have been found to consist of several in disguise, much as the alder and willow flycatchers were once considered to be one species, the Traill’s flycatcher.

6) Marsh wren (1989)

1989. Kroodsma, D. E. Two North American song populations of the Marsh Wren reach distributional limits in the Great Plains. Condor 91:332-340. (You could read the original research article here: Marsh Wren–1989 Condor)

I had learned that eastern and western marsh wrens were strikingly different from each other. West coast males sing 100 or more different songs with harsh broad-band rattles and buzzes and also sharp tonal notes, and they race through their large song repertoires, often answering each other with identical songs. Eastern males have about a third as many songs, with far less variability among songs, and they rarely answer each other with identical songs. Introductory calls to the songs also distinguished the two wrens.

variability among songs, and they rarely answer each other with identical songs. Introductory calls to the songs also distinguished the two wrens.

If the marsh wrens change gradually over distance from coast to coast, the variation would be considered “clinal,” the marsh wrens then all of the same species. But what if midcontinent I found an abrupt line where East met West, with little if any intermediate birds? Then I’d have strong evidence for two marsh wren species, not just one, in North America. And so it was that in 1986 I flew to the Great Plains, scouring the marshes of Iowa, South Dakota, and Nebraska for marsh wrens.

Two species! Absolutely no doubt, just as I had no doubt with the winter wren, though the official committees of ornithological organizations have yet to recognize the eastern marsh wren and western marsh wren as two separate species.

I could draw a line through eastern Nebraska, eastern birds to the east, western to the west. Only a couple of eastern birds were found to have settled a little farther west into predominantly western populations, but I found no evidence of hybrid singing behaviors, suggesting that these two wrens clearly recognized each other as two different species, even though we humans were a little slow to do so.

7) Eastern towhee (1994)

1994. Ewert, D. N., and D. E. Kroodsma. Song sharing and repertoires among migratory and resident Rufous-sided Towhees. Condor 96:190-196. (You could read the original research article here: Eastern Towhee–1994 Condor)

Why do neighboring males of some songbird species share identical learned songs but  neighboring males of other species not? In other words, why do some songbirds sing in dialects but others do not? Are migratory birds less likely to sing in dialects than sedentary, nonmigratory birds?

neighboring males of other species not? In other words, why do some songbirds sing in dialects but others do not? Are migratory birds less likely to sing in dialects than sedentary, nonmigratory birds?

In an attempt to answer this question, we studied the eastern towhee (then still called the rufous-sided towhee, as it had not yet been split from the western spotted towhee). Northern red-eyed populations are migratory, but the white-eyed birds of Florida are sedentary.

A Florida male, while living in a stable community and remaining on his territory for life, sings about eight different songs, most of them identical to the songs of immediate neighbors. In contrast, New York males sang half as many songs (3.5 average), and few songs were shared with neighbors.

Evidence from other species increasingly supports our conclusion, that dialects are more likely to develop in populations that do not migrate. Living in a stable community, in which singing males remain neighbors for life, seems to favor a system of singing interactions in which males learn their songs from each other and engage in countersinging duels using those learned songs.

8) Black-capped chickadee (1999)

1999. Kroodsma, D. E., B. E. Byers, S. L. Halkin, C. Hill, D. Minis, J. R. Bolsinger, J. Dawson, E. Donelan, J. Farrington, F. Gill, P. Houlihan, D. Innes, G. Keller, L. Macaulay, C. A. Marantz, J. Ortiz, P. K. Stoddard, and K. Wilda. Geographic variation in Black-capped Chickadee songs and singing behavior in North America. Auk 116:387-402. (You could read the original research article here:  Black-capped Chickadee–1999 Auk)

Black-capped Chickadee–1999 Auk)

The most common of birds often provides the greatest mysteries, and so it is with the black-capped chickadee, the official bird of my home state Massachusetts. This project was too good to do alone, so I invited a host of friends to join me in the fun. To launch this project, many of us gathered for a party on Martha’s Vineyard during May 1995.

One of the great puzzles is how these chickadees maintain the same stereotyped, learned song (hey-sweetie is my favored mnemonic) from the Atlantic to the Pacific. The song is simple, consisting primarily of two whistled notes, the first (hey) higher than the second (sweetie), and the second always has a brief, audible gap in the middle, making it a two-syllable sweetie. This simple song is transposed by a single male across a broad range of frequencies.

The exceptions to this hey-sweetie song are instructive. On Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket, two islands off the coast of Massachusetts, birds sing a different tune: 1) most island songs are monotonal, with all whistles in a song on the same frequency; 2) males sing two or more discretely different songs, with no transposing over frequency; 3) and songs occur in dialects, with three different dialects across the single small island of Martha’s Vineyard. Chickadees in western Oregon and Washington also have their own singing styles.

As with towhees, migration and isolation and sedentary habits probably play a role in the continent-wide variations in chickadee songs. Birds isolated by mountain ranges (the West) or on islands will be free to develop their own style of singing, and relatively small song dialects are the norm among many species under such situations. Migration and irruptions, with large scale unpredictable movements of chickadees throughout their geographic range, must play a role in the mixing of birds from many mainland locations, thus enabling birds to maintain a consistency in songs across the continent.

9) Sedge wren (1999)

1999. Kroodsma, D. E., P. A. Bedell, W.-c. Liu, and E. Goodwin. The ecology of song improvisation, as illustrated by North American Sedge Wrens (Cistothorus platensis). Auk 116:373-386. (You could read the original research article here: Sedge Wren–1999 Auk)

The marsh wren and sedge wren—two closely related species in the genus Cistothorus, yet their singing styles are so different. Neighboring marsh wrens have large repertoires of identical songs, revealing that they’ve learned them from each other. Neighboring sedge wrens can have 100 or more songs, but they’re all unique, none of them shared with neighbors? Why the difference?

singing styles are so different. Neighboring marsh wrens have large repertoires of identical songs, revealing that they’ve learned them from each other. Neighboring sedge wrens can have 100 or more songs, but they’re all unique, none of them shared with neighbors? Why the difference?

To understand better how these wrens acquire their songs, we raised some young birds in the laboratory. Marsh wrens learned songs from loudspeakers and from each other, thus confirming the importance of song learning in their natural history, but sedge wrens learned nothing, each male instead improvising or inventing his own repertoire of songs. It’s the “snow flake strategy,” in that all songs sound like a sedge wren, but no two are alike.

In our field surveys, aided by numerous volunteers, we found that sedge wrens seem to be semi-nomadic. They arrive to breed at more northern latitudes during May, which is typical of many songbirds, but then the sedge wrens often disappear, apparently breeding at a second more southerly latitude from mid-June through July and sometimes into September or October. Not living in or returning to stable singing groups from one breeding attempt to the next, sedge wrens have come to improvise a large repertoire of generalized songs that are instantly recognizable anywhere in the geographic range of the species. Their style of song development and singing thus meshes nicely with their natural history.

10) Three-wattled bellbird (2013)

2013. Kroodsma, D., D. Hamilton, et al. “Behavioral evidence for song learning in the suboscine bellbirds (Procnias spp.; Cotingidae). The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 125: 1-14. (You could read the original research article here: Three-wattled Bellbird–2013 Wilson Journal)

One of the most frequently asked questions about birdsong is this: Why do some groups learn  their songs (much as we humans learn to speak) and others don’t? Songbirds, parrots, and hummingbirds learn, we know, but good evidence for other groups is lacking.

their songs (much as we humans learn to speak) and others don’t? Songbirds, parrots, and hummingbirds learn, we know, but good evidence for other groups is lacking.

Flycatchers have innate songs, as I’ve shown in the laboratory. Flycatchers are suboscines, members of a large tropical lineage that includes woodcreepers, antbirds, tapaculos, manakins, cotingas, and a few others, and it seems that songs of these other suboscines are innate as well. That would be a neat difference between the song-learning songbirds and the non-learning suboscines.

But it’s not so! In a study spanning nearly 20 years, and capitalizing on recordings going back to the mid-1970’s, we have verified that males in one small group of suboscines, the bellbirds, learn their songs. That’s exciting, because bellbirds are cotingas and presumably evolved from non-learning ancestral suboscines, and these bellbirds provide only the fourth independent evolutionary origin of song learning among birds.

Our evidence: A captive-reared bare-throated bellbird in Brazil learned the calls of a Chopi blackbird. From Nicaragua to Costa Rica to Panama, songs of three-wattled bellbirds occur in three learned dialects. Young males babble in subsong as they learn their songs, just as do young songbirds. About half of young males at Monteverde, Costa Rica, are bilingual, learning the songs of two dialects (much as young songbirds “overproduce” before they settle on their adult songs), before they choose one dialect to sing as an adult. Adults listen to each other constantly, visiting each other on their singing perches, learning and relearning each others’ songs at a pace such that songs of all males change noticeably and change together, in unison, from one year to the next.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Academic resume

Donald E. Kroodsma

Education

Academic Appointments

Professional Societies

Professional Service

Courses taught (University of Massachusetts)

Graduate student education

Research Interests

Post-graduate Fellowships, Grants, or Awards

Publications in refereed journals

Commentaries, semi-popular articles

Theses, books, book chapters

Book reviews

Education

1972 Ph. D., Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon (Woodrow Wilson Fellow). John A. Wiens, advisor.

1972 Organization for Tropical Studies, University of Costa Rica, San Jose

1968 University of Michigan Biological Station, Pellston, Michigan

1968 B.A., Hope College, Holland, Michigan (magna cum laude; double major, in Chemistry & Biology)

Academic Appointments

Professor Emeritus 2004-present

Professor, Univ. of Massachusetts, Amherst 1987-2003

Associate Professor, Univ. of Massachusetts, Amherst 1980-1987

Assistant Professor, Rockefeller University 1974-1980

Postdoctoral Fellow, Rockefeller University 1972-1974

Professional Societies

American Ornithologists’ Union (Fellow)

Animal Behaviour Society (Fellow)

Wilson Ornithological Society

Professional Service

Associate Editor, Birds of North America. 1996-2003

Associate Editor, The Auk. 1998-2002

Councilor or Secretary, Association of Field Ornithologists. 1996-2003.

American Ornithologists’ Union. Brewster and Coues award committee (1989, 1996-1998, Chair 1998). Van Tyne and Wetmore Awards Committee, Biography Committee (1982-1984)

Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, Administrative Board (1990-1995)

Member, Advisory Board to Executive Director of Hitchcock Center

Rainforest Expeditions. Volunteer instructor in Peruvian Amazon (August 1995)

Consulting Editor, “Journal of Comparative Psychology” (1989-1995)

Host, Northeastern Regional Animal Behaviour Society Meetings, Amherst (1991)

Cooper Ornithological Society, Painton (best paper) Award Committee (1989)

Editorial Board of “Animal Behaviour” (1982-1988)

Editorial Board of “Current Ornithology” (1981-1987)

National Science Foundation, Psychobiology advisory panel (1980, 1985-1988)

Courses taught (University of Massachusetts)

Biology. 544, Ornithology. For majors. Taught each spring semester.

Biology. 750, Advanced Animal Behavior. Taught every third fall semester.

Biology. 789, “Communicate,” a graduate level course on how to communicate research both orally and in writing. Taught every third fall semester.

Biology. 312, Writing in Biology. Taught every third fall semester.

Biology. 263, Biology of Birds. An occasional course on birds for nonmajors.

Graduate student education (Ph. D. students whose committees I have chaired or co-chaired).

Albano, D. J. A behavioral ecology of the Belted Kingfisher (Ceryle alcyon)

Armstrong, T. A. Female red-winged blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus) vocalizations: Variation and ontogeny

Belinski, Kara. Sexual selection in song and plumage among Chestnut-sided Warblers

Byers, B. E. Development, variation, and use of two song categories by chestnut-sided warblers

Goodale, E. B. Interspecific communication in mixed-species bird flocks of a Sri Lankan rain forest

Goodwin, E. A. The ecology and development of alternative vocal learning programs in birds

Highsmith, R. T. Function, form, and recognition of the songs of golden-winged warblers (Vermivora chrysoptera) and blue-winged (V. pinus) warblers

Houlihan, P. W. The singing behavior of prairie warblers (Dendroica discolor)

Johnson, S. L. Song learning and syntax patterns in the American robin and the soil characteristics of bank swallow nest sites

Liu, W-c. Development, variation, and use of songs by chipping sparrows

Marantz, C. A. Patterns of geographic variation in the songs of a neotropical lowland bird

Razafimahaimodison, Jean-Claude. Impacts of habitat disturbance, including ecotourism activities, on breeding behavior and success of the Pitta-like Ground Roller, Atelornis pittoides, an endangered birds species in the eastern rainforest of Ranomafana National Park, Madagascar

Spector, D. A. The singing behavior of Yellow Warblers.

Staicer, C. A. The role of male song in the socioecology of the tropical resident Adelaide’s warbler (Dendroica adelaidae)

Werner, T. K. Behavioral, individual feeding specializations by Pinaroloxias inornata, the Darwin’s finch of Cocos Island, Costa Rica

Research Interests

Animal Communication, especially the ecology, evolution, ontogeny, and neural control of vocal behavior in birds.

Post-graduate Fellowships, Grants, or Awards

2014. Margaret Morse Nice award, the “premiere ornithological award” from the Wilson Ornithological Society.

2006. The 2006 John Burroughs medal for natural history writing, for The Singing Life of Birds.

2006. American Birding Association, the Robert Ridgway Distinguished Service Award, “given for excellence in publications pertaining to field ornithology.”

2003. Elliott Coues Award, awarded by the American Ornithologists’ Union “for meritorious contributions having an important influence on the study of birds in the Western Hemisphere.” . . . “Donald E. Kroodsma is the current reigning authority on the biology of avian vocal behavior . . .”

1995-1999. National Science Foundation (NSF) Grant, “Collection improvement for the Cornell Library of Natural Sounds.” (G. F. Budney and D. E. Kroodsma, co-PIs).

1995. Faculty Fellowship Award, University of Massachusetts. For “Outstanding Research and Scholarship.”

1994-1999. NSF Grant IBN-9408520, “Ecology of Passerine Song Development.”

1991-1993. NSF Grant BNS-91111666, “Significance and Consequences of Avian Vocal Development.”

1988-1991. NSF Grant BNS-8812084, “Significance and Consequences of Avian Vocal Development.”

1985-1988. NSF Grant BNS-8506996, “Significance and Consequences of Avian Vocal Development.”

1982-1985. NSF Grant, BNS-8201085, “The Biological Significance of Avian Vocal Learning.”

1980-1982. NSF Grant, BNS-8040282, “Significance of Sensitive Periods in Avian Vocal Learning.”

1980-1981. Biomedical Research Support Grant, U. Mass.

1978-1980. NSF Grant, BNS-7802743, “Significance of Sensitive Periods in Avian Vocal Learning.”

1976-1979. NSF Grant, BNS-7607704, “Significance of Avian Vocal Learning.”

1973-1974. NIMH postdoctoral fellow, Rockefeller University.

1972-1973. NIH postdoctoral fellow, Rockefeller University.

Publications in refereed journals

2013. Kroodsma, D., D. Hamilton, et al. “Behavioral evidence for song learning in the suboscine bellbirds (Procnias spp.; Cotingidae). The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 125: 1-14.

2009. Byers, B. E. and D. E. Kroodsma (2009). Female mate choice and songbird song repertoires. Animal Behaviour 77(1): 13-22.

2008. Wheelwright, N. T., M. B. Swett, I. l. Leven, D. E. Kroodsma, C. R. Freeman-Gallant, and H. Williams. (2008). The influence of different tutor types on song learning in a natural bird population. Animal Behaviour 75: 1479-1493.

2007. Saranathan, V., D. Hamilton, G. V. N. Powell, D. E. Kroodsma, and R. O. Prum.. (2007). Genetic evidence supports song learning in the three-wattled bellbird Procnias tricarunculata (Cotingidae). Molecular Ecology 16(17): 3689-3702.

2007. Liu, W. C. and D. E. Kroodsma (2007). Dawn and daytime singing behavior of chipping sparrows (Spizella passerina). Auk 124(1): 44-52.

2006. Liu, W. C. and D. E. Kroodsma (2006). Song learning by Chipping Sparrows: When, where, and from whom. Condor 108(3): 509-517.

2002. Kroodsma, D. E., R. W. Woods, and E. A. Goodwin. (2002). Falkland Island Sedge Wrens (Cistothorus platensis) imitate rather than improvise large song repertoires. Auk 119(2): 523-528.

2001. Kroodsma, D. E., K. Wilda, et al. (2001). Song variation among Cistothorus wrens, with a focus on the Merida Wren. Condor 103(4): 855-861.

2001. Kroodsma, D. E., B. E. Byers, E. Goodale, S. Johnson, W.-c Liu. (2001). Pseudoreplication in playback experiments, revisited a decade later. Animal Behaviour 61: 1029-1033.

2001. Hartman, V. N., M. A. Miller, D. F. clayton, W.-c. Liu, D. E. Kroodsma, and E. A. Brenowitz. (2001). Testosterone regulates alpha-synuclein mRNA in the avian song system. Neuroreport 12(5): 943-946.

2000. Rivers, J. W. and D. E. Kroodsma (2000). Singing behavior of the Hermit Thrush. Journal of Field Ornithology 71(3): 467-471.

2000. Kroodsma, D. E. and B. E. Byers (2000). Suggestions for slides at scientific meetings. Auk 117(3): 831-835.

2000. Kroodsma, D. E. (2000). A quick fix for figure legends and table headings. Auk 117(4): 1081-1083.

2000. Airey, D. C., D. E. Kroodsma, and T. J. DeVoogd. (2000). Differences in the complexity of song tutoring cause differences in the amount learned and in dendritic spine density in a songbird telencephalic song control nucleus. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory 73(3): 274-281.

1999. Liu, W. C. and D. E. Kroodsma (1999). Song development by chipping sparrows and field sparrows. Animal Behaviour 57: 1275-1286.

1999. Kroodsma, D. E., J. Sanchez, D. W. Stemple, E. Goodwin, M. L. Da Silva, and J. M. E. Vielliard, 1999. Sedentary life style of neotropical sedge wrens promotes song imitation. Animal Behaviour 57: 855-863.

1999. Bradbury, J., G. F. Budney, D. W. Stemple, and D. E. Kroodsma. Organizing and archiving private collections of tape recordings. Animal Behaviour 57: 1343-1344.

1999. Kroodsma, D. E., P. A. Bedell, W.-c. Liu, and E. Goodwin. The ecology of song improvisation, as illustrated by North American Sedge Wrens (Cistothorus platensis).

1999. Kroodsma, D. E., B. E. Byers, S. L. Halkin, C. Hill, D. Minis, J. R. Bolsinger, J. Dawson, E. Donelan, J. Farrington, F. Gill, P. Houlihan, D. Innes, G. Keller, L. Macaulay, C. A. Marantz, J. Ortiz, P. K. Stoddard, and K. Wilda. Geographic variation in Black-capped Chickadee songs and singing behavior in North America. Auk 116:387-402.

1997. Kroodsma, D. E., P. W. Houlihan, P. A. Fallon, and J. A. Wells. Song development by Grey Catbirds. Animal Behaviour 54:457-464.

1995. Brenowitz, E. A., K. Lent, and D. E. Kroodsma. Brain space for learned song in birds develops independently of song learning. Journal of Neuroscience 15:6281-6286.

1995. Kroodsma, D. E., D. J. Albano, P. W. Houlihan, and J. A. Wells. Song development by Black-capped Chickadees (Parus atricapillus) and Carolina Chickadees (P. carolinensis). Auk 112:29-43.

1994. Brenowitz, E. A., B. Nalls, D. E. Kroodsma, and C. Horning. Female Marsh Wrens do not provide evidence of anatomical specializations for perception of male song. Journal of Neurobiology 25:197-108.

1994. Ewert, D. N., and D. E. Kroodsma. Song sharing and repertoires among migratory and resident Rufous-sided Towhees. Condor 96:190-196.

1994. Kroodsma, D. E., and F. C. James. Song variation within and among populations of Red-winged Blackbirds. Wilson Bulletin 106:156-162.

1993. Kroodsma, D. E. Ecology of passerine song development. A personal perspective. Etología 3:113-123.

1993. Gahr, M., H. R. Güttinger, and D. E. Kroodsma. Estrogen receptors in the avian brain: survey reveals general distribution and forebrain areas unique to songbirds. Journal of Comparative Neurology 327:112-122.

1992. Byers, B. E., and D. E. Kroodsma. Development of two song categories by chestnut-sided warblers. Animal Behaviour 44:799-810.

1992. Kroodsma, D. E. Much ado creates flaws. Animal Behaviour 44:580-582.

1991. Kroodsma, D. E., and H. Momose. Songs of the Japanese population of the Winter Wren (Troglodytes troglodytes). Condor 93:424-432.

1991. Brenowitz, E. A., B. Nalls, J. C. Wingfield, and D. E. Kroodsma. Seasonal changes in avian song nuclei without seasonal changes in song repertoire. Journal of Neuroscience 11:1367-1374.

1991. Kroodsma, D. E., and M. Konishi. A suboscine bird (eastern phoebe, Sayornis phoebe) develops normal song without auditory feedback. Animal Behaviour 42:477-487.

1991. Kroodsma, D. E.. and B. E. Byers. The function(s) of bird song. American Zoologist 31:318-328.

1990. Kroodsma, D. E. Using appropriate experimental designs for intended hypotheses in ‘song’ playbacks, with examples for testing effects of repertoire sizes. Animal Behaviour 40:1138-1150.

1990. Spector, D. A., L. K. McKim, and D. E. Kroodsma. Yellow Warblers are able to learn songs and situations in which to use them. Animal Behaviour 38:723-725.

1990. Kroodsma, D. E. Patterns in songbird singing behavior: Hartshorne vindicated. Animal Behaviour 39:994-996.

1989. Kroodsma, D. E. Inappropriate experimental designs impede progress in bioacoustic research: a reply. Animal Behaviour 38:717-719.

1989. Kroodsma, D. E., R. C. Bereson, B. E. Byers, and E. Minear. Use of song types by the Chestnut-sided Warbler: evidence for both intrasexual and intersexual functions. Canadian Journal of Zoology 67:447-456.

1989. Kroodsma, D. E. Two North American song populations of the Marsh Wren reach distributional limits in the Great Plains. Condor 91:332-340.

1989. Kroodsma, D. E. Suggested experimental designs for song playbacks. Animal Behaviour 37:600-609.

1989. Kirn, J. R., R. P. Clower, D. E. Kroodsma, and T. J. DeVoogd. Song-related brain regions in the Red-winged Blackbird are affected by sex and season but not repertoire size. Journal of Neurobiology 20:139-163.

1989. Kroodsma, D. E. Male Eastern Phoebes (Tyrannidae, Passeriformes) fail to imitate songs. Journal of Comparative Psychology 103:227-232.

1988. Kroodsma, D. E. Song types and their use: developmental flexibility of the male blue-winged warbler. Ethology 79:235-247.

1987. Kroodsma, D. E., and J. Verner. Use of song repertoires among marsh wren populations. Auk 104:63-72.

1987. Kroodsma, D. E., V. A. Ingalls, T. W. Sherry, and T. K. Werner. Songs of the Cocos Flycatcher: vocal behavior of a suboscine on an isolated oceanic island. Condor 89:75‑84.

1987. Bryan, K., R. Moldenhauer, and D .E. Kroodsma. Geographic uniformity in songs of the Prothonotary Warbler. Wilson Bulletin 99:369-376.

1986. Kroodsma, D. E. Song development by castrated Marsh Wrens. Animal Behaviour 34:1572-1575.

1986. Kroodsma, D. E. Design of song playback experiments. Auk 102:640‑642.

1985. Kroodsma, D. E. Geographic variation in songs of the Bewick’s wren: a search for correlations with avifaunal complexity. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 16:143-150.

1985. Kroodsma, D. E., and R. Canady. Differences in repertoire size, singing behavior, and associated neuroanatomy among Marsh Wren populations have a genetic basis. Auk 102:439-446.

1985. Kroodsma, D. E. Development and use of two song forms by the Eastern Phoebe. Wilson Bulletin 97:21-29.

1984. Kroodsma, D. E. Songs of the Alder Flycatcher (Empidonax alnorum) and Willow Flycatcher (Empidonax traillii) are innate. Auk 101:13-24.

1984. Kroodsma, D. E., and R. Pickert. Sensitive phases for song learning: effects of social interaction and individual variation. Animal Behaviour 32:389-394.

1984. Kroodsma, D. E., and R. Pickert. Repertoire size, auditory templates, and selective vocal learning in songbirds. Animal Behaviour 32:395‑399.

1984. Canady, R. C., D. E. Kroodsma, and F. Nottebohm. Population differences in complexity of a learned skill are correlated with the brain space involved. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 81:6232-6234.

1984. Kroodsma, D. E., W. R. Meservey, A. L. Whitlock, and W. M. VanderHaegen. Blue-winged Warblers (Vermivora pinus) “recognize” dialects in Type II but not Type I songs. Behavioural Ecology and Sociobiology 15:127-132.

1983. Kroodsma, D. E., W. R. Meservey, and R. Pickert. Vocal learning in the Parulinae. Wilson Bulletin 95:138-140.

1983. Kroodsma, D. E. The ecology of avian vocal learning. BioScience 33:165-171.

1981. Kroodsma, D. E. Geographical variation and functions of song types in warblers (Parulidae). Auk 98:743-751.

1980. Kroodsma, D. E., and R. Pickert. Environmentally dependent sensitive periods for avian vocal learning. Nature 288:477-479.

1980. Kroodsma, D. E. Winter wren singing behavior: a pinnacle of song complexity. Condor 82:356-365.

1979. Kroodsma, D. E. Vocal dueling among male marsh wrens: evidence for ritualized expressions of dominance/subordinance. Auk 96:506-515.

1978. Kroodsma, D. E., and J. Verner. Complex singing behaviors among Cistothorus wrens. Auk 95:703-716.

1978. Kroodsma, D. E. Continuity and versatility in bird song; support for the monotony threshold hypothesis. Nature 274:681-683.

1977. Kroodsma, D. E., and L. D. Parker. Vocal virtuosity in the Brown Thrasher. Auk 94:783-785.

1977. Kroodsma, D. E. Correlates of song organization among North American wrens. American Naturalist 111:995-1008.

1977. Kroodsma, D. E. A re-evaluation of song development in the Song Sparrow. Animal Behaviour 25:390-399.

1976. Kroodsma, D. E. Reproductive development in a female songbird: differential stimulation by quality of male song. Science 192:574-575.

1976. Kroodsma, D. E. The effect of large song repertoires on neighbor recognition in male Song Sparrows. Condor 78:97-99.

1975. Kroodsma, D. E. Song patterning in the Rock Wren. Condor 77:294-303.

1975. Kroodsma, D. E. Foraging distances of male Euglossine bees in pollination of orchids. Biotropica 67:71-72.

1974. Kroodsma, D. E. Song learning, dialects, and dispersal in the Bewick’s Wren. Zeitschrift für Tierpsychol. 35:352-380.

1973. Kroodsma, D. E. Coexistence of Bewick’s Wrens and House Wrens in Oregon. Auk 90:341-352.

1972. Kroodsma, D. E. Variations in the songs of Vesper Sparrows in Oregon. Wilson Bulletin 84:174-178.

1972. Kroodsma, D. E. Bigamy in the Bewick’s Wren. Auk 89:185-187.

1971. Kroodsma, D. E. Song variations and singing behavior in the Rufous-sided Towhee, Pipilo erythrophthalmus oregonus. Condor 73:303-308.

Commentaries, semi-popular articles, and miscellaneous non-refereed publications:

2010. Kroodsma, D. E. (2010). Being there. Birding March 2010: 46-53.

2001. Kroodsma, D. E. (2001). Surfing the dawn. The Living Bird, Cornell University Laboratory of Ornithology 20(Spring 2001): 38-42

1999. Byers, B. E. and D. E. Kroodsma (1999). They sang it their way. The deviant chickadees of Martha’s Vineyard. Bird Observer 27: 4-11.

1998. Kroodsma, D. E. Getting started—listening to your friends. Birder’s World 12(6):20-21.

1998. Budney, G. F. and D. E. Kroodsma. Bird Talk—The Dragonfly Challenge. Dragonfly Jan/Feb 1998:15-16.

1997. Kroodsma, D. E. A wren’s eye view. Birder’s World 11 (1): 40-44

1996. Kroodsma, D. E. A song of their own. Living Bird 15 (3): 10-17.

1996. Kroodsma, D. E. Marsh Wren song. Birder’s World 10 (4): 26.

1995. Brenowitz, E. A., K. Lent, and D. E. Kroodsma. Brain space for learned song in birds develops independently of song learning. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts, 21:962.

1994. Kroodsma, D. E. Beyond bird names. Birder’s World Oct. 8 (5):36-41.

1993. Kroodsma, D. E. Cousin Songbird. Birder’s World Oct. 7 (5):17-21.

1989. Hill, K. M., D. E. Kroodsma, and T. J. DeVoogd. Changed daylength causes changes in dendritic structure in a song-related brain region in red-winged blackbirds. Abstract, Society for Neuroscience.

1989. Kroodsma, D. E. What, when, where, and why warblers warble. Natural History May 1989:50-59.

1989. Kroodsma, D. E. Animal Song. Pages 88-90 in E. Brounow (Ed.) International Encyclopedia of Communications. Oxford University Press.

1988. Kroodsma, D. E. Two species of Marsh Wren (Cistothorus palustris) in Nebraska? Birding 20:371-374. (reprinted from The Nebraska Bird Review)

1988. Kroodsma, D. E. Behavioral ontogeny research: no pain, no gain? Behavioral and Brain Sciences 11:639-640.

1988. Kroodsma, D. E. Two species of marsh wren (Cistothorus palustris) in Nebraska? Nebraska Bird Review 56:40-42.

1987. Kroodsma, D. E. Singing in the brain. Birder’s World 1(2):4-7.

1986. Kroodsma, D. E. The spice of bird song. Living Bird Quarterly 5:12‑16.

1985. Kroodsma, D. E. Limited dispersal between dialects?: hypotheses testable in the field. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 8:108-109.

1983. Kroodsma, D. E. Marsh Wrenditions. Natural History 92:42-47.

1983. Kroodsma, D. E. The ecology of avian vocal learning. The Dominion Roller Canary News, Volume 40 (reprinted from BioScience 33:165-171)

1981. Canady, R., D. E. Kroodsma, and F. Nottebohm. Significant difference in volume of song control nuclei is associated with variance in song repertoire in a free ranging song bird. Neurosciences Abstracts 1981:845.

1977. Kroodsma, D. E. Reproductive development in a female songbird: differential stimulation by quality of male song. Reprinted in NIROC Bulletin.

Thesis, books, book chapters (additional non-refereed publications)

2009. Kroodsma, D. E. Birdsong by the Seasons. A Year of Listening to Birds. Boston, Massachusetts, Houghton-Mifflin Harcourt Co.

2008. Kroodsma, D. E. The Backyard Birdsong Guide. Western North America. San Francisco, California, Chronicle Books.

2008. Kroodsma, D. E. The Backyard Birdsong Guide. Eastern and Central North America. San Francisco, California, Chronicle Books.

2005. Kroodsma, D. E. The Singing Life of Birds. The Art and Science of Listening to Birdsong. Boston, Massachusetts, Houghton-Mifflin Co.

2004. Kroodsma, D. E. The diversity and plasticity of song development. Nature’s Music. Pp. 108-131 in The Science of Birdsong. (P. Marler and H. Slabbekoorn, eds). Amsterdam, Netherlands, Elsevier Academic Press.

2002. Weckstein, J., D. E. Kroodsma, and R. Faucet. Fox Sparrow (Passerella iliaca). The Birds of North America, No. A. Poole and F. Gill. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, The Birds of North America, Inc.

2002. The vocal behavior of birds. in Home-study Course, Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology. Ithaca, New York.

2002. MacWhirter, B., P. Austin-Smith, Jr., and D. E. Kroodsma. Sanderling (Calidris alba). The Birds of North America, No. 653. A. Poole and F. Gill, The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; The American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, D. C.: 1-28.

2002. Herkert, J., P. Vickery, and D. E. Kroodsma. Henslow’s Sparrow (Ammodramus henslowii). The Birds of North America, No. 672. A. Poole and F. Gill. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, The Birds of North America, Inc.

2002. Hejl, S. J., J. A. Holmes, and D. E. Kroodsma. Winter Wren (Troglodytes troglodytes). The Birds of North America, No. 623. A. Poole and F. Gill. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, The Birds of North America, Inc.: 1-32.

2001. Herkert, J. and Kroodsma, D. E. The Sedge Wren (Cistothorus platensis). In The Birds of North America, No. 582. The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, and The American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington D.C.

2001. Baptista, L. F. and D. E. Kroodsma Avian Bioacoustics, A tribute to Luis Felipe Baptista. Handbook of Birds of the World. Vol. 6. J. del Hoyo and A. Elliott. Barcelona, Lynx Edicions: 11-52.

2000. Lowther, P. and Kroodsma, D. E. The Rock Wren (Salpinctes obsoletus). In The Birds of North America, No. 486.The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, and The American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington D.C.

1999 1999. Kroodsma, D. E. Making ecological sense of song development by songbirds. P. 319-342 in Neurobehavioral Mechanisms of Communication (M. Konishi and M. Hauser, Eds.). The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

1998. Kroodsma, D. E., and B. E. Byers. Oscine song repertoires: an ethological approach to studying cognition. in Animal Cognition in Nature (R. Balda, A. Kamil, and I. Pepperberg, Eds.) Academic Press, London, England.

1997. Kroodsma, D. E., and J. Verner. The Marsh Wren (Cistothorus palustris). In The Birds of North America, No. 308. The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, and The American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington D.C.

1996. Kroodsma, D. E. and E. H. Miller (Eds.). Ecology and Evolution of Acoustic Communication in Birds. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY.

1996. Kroodsma, D. E. Ecology of passerine song development. Pages 3-19 in Ecology and Evolution of Acoustic Communication in Birds (D. E. Kroodsma and E. H. Miller, Eds.). Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY.

1996. Kroodsma, D. E., J. M. E. Vielliard, and F. G. Stiles. Study of bird sounds in the Neotropics: Urgency and opportunity. Pages 269-281 in Ecology and Evolution of Acoustic Communication in Birds (D. E. Kroodsma and E. H. Miller, Eds.). Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY.

1996. Brenowitz, E. A., and D. E. Kroodsma. The neuroethology of bird song. Pages 285-304 in Ecology and Evolution of Acoustic Communication in Birds (D. E. Kroodsma and E. H. Miller, Eds.). Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY.

1996. Kroodsma, D. E., G. F. Budney, R. W. Grotke, J. Vielliard, S. L. L. Gaunt, R. Ranft, and O. D. Veprintseva. Natural Sound archives: guidance for recordists and a request for cooperation. Pages 474-486 in Ecology and Evolution of Acoustic Communication in Birds (D. E. Kroodsma and E. H. Miller, Eds.). Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY.

1992. McGregor, P. K., C. K. Catchpole, T. Dabelsteen, J. B. Falls, L. Fusani, H. C. Gerhardt, F. Gilbert, A. G. Horn, G. M. Klump, D. E. Kroodsma, M. M. Lambrechts, K. E. McComb, D. A. Nelson, I. M. Pepperberg, L. Ratcliffe, W. A. Searcy, and D. M. Weary. Design of playback experiments: the Thornbridge Hall NATO ARW consensus. Pages 1-9 in Playback and Studies of Animal Communication (P. K. McGregor, Ed.). Plenum Press, New York.

1990. Kroodsma, D. E. How the mismatch between the experimental design and the intended hypothesis limits confidence in knowledge, as illustrated by an example from bird-song dialects. Pages 226-245 in Interpretation and explanation in the study of animal behavior. Vol. 2. (M. Bekoff and D. Jamieson, Eds.). Westview Press, Boulder, Colorado.

1988. Kroodsma, D. E., and C. K. Catchpole. Intrasexual and intersexual functions of bird song. Introduction and concluding remarks. Pages 1357, 1398-1399 in Acta XIX Congressus Internationalis Ornithologica, Vol. I. (H. Ouellet, Ed.) University of Ottawa Press, Ottawa.

1988. Kroodsma, D. E. Contrasting styles of song development and their consequences among the Passeriformes. Pp. 157-184 in Evolution and Learning (R. C. Bolles and M. D. Beecher, Eds.). Erlbaum Assoc., Inc., Hillsdale, New Jersey.

1985. Kroodsma, D. E., M. C. Baker, L. F. Baptista, and L. Petrinovich. Vocal “dialects” in Nuttall’s White-crowned Sparrow. Current Ornithology 2:103-133.

1984. Kroodsma, D. E., et al. Biology of learning in nonmammalian vertebrates. Group report. Pp. 399-418 in The Biology of Learning (P. Marler and H. S. Terrace, Eds.). Dahlem Konferenzen, Berlin.

1983. Kroodsma, D. E. Bird vocalizations: a commentary. Pp. 506-511 in Perspectives in Ornithology for the AOU Centennial (G. A. Clark, Jr., and A. Brush, Eds.). Cambridge University Press, New York.

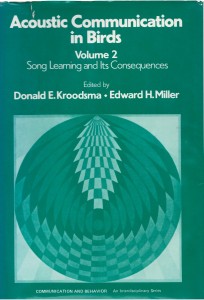

1982. Kroodsma, D. E., and E. H. Miller (Eds.). Acoustic communication in birds. Vol. 1. Production, perception, and design features of sounds. New York, Academic Press.

1982. Kroodsma, D. E., and E. H. Miller (Eds.). Acoustic communication in birds. Vol. 2. Song learning and its consequences. Academic Press, New York.

1982. Kroodsma, D. E. Learning and the ontogeny of sound signals in birds. Pages1-23 in Acoustic Communication in Birds, Vol. 2 (D. E. Kroodsma and E. H. Miller, Eds.). Academic Press, New York.

1982. Kroodsma, D. E. Song repertoires: problems in their definition and use. Pages 125-146 in Acoustic Communication in Birds, Vol. 2 (D. E. Kroodsma and E. H. Miller, Eds.). Academic Press, New York.

1982. Kroodsma, D. E., and J. R. Baylis. Appendix: a world survey of evidence for vocal learning in birds. Pages 311-337 in Acoustic communication in birds, Vol. 2 (D. E. Kroodsma and E. H. Miller, Eds.). Academic Press, New York.

1981. Ontogeny of bird song. Pages 518-532 in Early development in man and animals (K. Immelmann, G. Barlow, L. Petrinovich, and M. Main, Eds.). The Bielefeld Project. Cambridge University Press.

1980. Krebs, J. R., and D. E. Kroodsma. Repertoires and geographical variation in bird song. Pages 143-177 in Advances in the Study of Behavior, Vol. 11 (J. S. Rosenblatt, R. A. Hinde, C. Beer, and M. C. Busnel, Eds.). Academic Press, New York.

1979. Kroodsma, D. E. Habitat values for nongame wetland birds. Pages 320-329 in Wetland functions and values: the state of our understanding (P. E. Greeson, J. R. Clark, and J. E. Clark, Eds.). American Water Resources Association, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

1978. Kroodsma, D. E. Aspects of learning in the ontogeny of bird song: where, from whom, when, how many, which, and how accurately? Pages 215-230 in Development of Behavior (G. Burghardt and M. Bekoff, Eds.). Garland Publishing Co., New York.

1972. Kroodsma, D. E. Singing behavior of the Bewick’s Wren: development, dialects, population structure, and geographical variation. Ph. D. Dissertation, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon.

Book Reviews

1998. Kroodsma, D. E. Social influences on vocal development, by C. T. Snowdon and M. Hausberger (Eds.). Auk.

1997. Kroodsma, D. E. The minds of birds, by Alexander F. Skutch. BioScience.

1989. Kroodsma, D. E. Bird songs in Cuba/Cantos de Aves en Cuba. Auk 106:529.

1989. Kroodsma, D. E. Voices of the wrens: Family Troglodytidae. ARA Records, Gainesville. Auk 106:172-173.

1988. Kroodsma, D. E. The unknown music of birds. Auk 105:607.

1986. Kroodsma, D. E. Voices of New World thrushes. ARA Records, Gainesville. Auk 103:653.

1985. Kroodsma, D. E. Voices of the New World jays, crows, and their allies. Family Corvidae. ARA Records, Gainesville. Auk 102:433.

1985. Kroodsma, D. E. The starling, by C. Feare, Oxford University Press, New York. Auk 102:912-913.

1985. Kroodsma, D. E. Bird sounds and their meaning, by R. Jellis, Cornell Univ. Press, Ithaca. Auk 102:437-438.

1983. Kroodsma, D. E., and D. A. Spector. Une journee chez les oiseaux, by P. Morency, La Société zoologique de Québec. Auk 100:792.

1983. Kroodsma, D. E. An introduction to behavioral ecology, by J. R. Krebs and N. B. Davies (Eds.). Sunderland, MA, Sinauer Associates, Inc. Auk 100:785-787.

1977. Kroodsma, D. E. Bird sounds, by G. A. Thielcke, Univ. of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 1976. Quarterly Review of Biology.

1975. Kroodsma, D. E. The life of birds, by J. Dorst, Columbia University Press, New York, 1974. Quarterly Review of Biology.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Professional edited books

On two occasions, my colleague Edward H. (“Ted”) Miller and I gathered the best and brightest bioacousticians who studied birdsong and invited them to contribute a chapter to volumes that we edited. In 1982, two volumes on Acoustic Communication in Birds were published by Academic Press, and in 1996 a single larger volume entitled Ecology and Evolution of Acoustic Communication in Birds was published by Cornell University Press.

At the time, these edited books were an exciting tour through the science of “avian bioacoustics,” and they still contain an abundance of timeless material for the serious scientist. The contents of these three volumes are listed below:

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

1982. Kroodsma, D. E., and E. H. Miller (Eds.). Acoustic communication in birds. Vol. 1. Production, perception, and design features of sounds. New York, Academic Press.

1982. Kroodsma, D. E., and E. H. Miller (Eds.). Acoustic communication in birds. Vol. 1. Production, perception, and design features of sounds. New York, Academic Press.

Contents

1. Factors to consider in recording avian sounds, by David C. Wickstrom

2. The structural basis of voice production and its relationship to sound characteristics, by John H. Brackenbury

3. Neural control of passerine song, by Arthur P. Arnold

4. Auditory perception in birds, by Robert J. Dooling

5. Adaptations for acoustic communication in birds: sound transmission and signal detection, by R. Haven Wiley and Douglas G. Richards

6. Grading, discreteness, redundancy, and motivation-structural rules, by Eugene S. Morton

7. The coding of species-specific characteristics in bird sounds, by Peter H. Becker

8. Character and variance shift in acoustic signals of birds, by Edward H. Miller

9. The evolution of bird sounds in relation to mating and spacing behavior, by Clive K. Catchpole

Taxonomic index

Subject index

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

1982. Kroodsma, D. E., and E. H. Miller (Eds.). Acoustic communication in birds. Vol. 2. Song learning and its consequences. Academic Press, New York.

1982. Kroodsma, D. E., and E. H. Miller (Eds.). Acoustic communication in birds. Vol. 2. Song learning and its consequences. Academic Press, New York.

Contents

1. Learning and the ontogeny of sound signals in birds, by Donald E. Kroodsma

2. Subsong and plastic song: their role in the vocal learning process, by Peter R. Marler and Susan Peters

3. Avian vocal mimicry; its function and evolution

4. The ecological and social significance of duetting, by Susan M. Farabaugh

5. Song repertoires: problems in their definition and use, by Donald E. Kroodsma

6. Microgeographic and macrogeographic variation in acquired vocalizations of birds, by Paul C. Mundinger

7. Genetic population structure and vocal dialects in Zonotrichia (Emberizidae), by Myron C. Baker

8. Individual recognition by sound in birds, by J. Bruce Falls

9. Conceptual issues in the study of communication, by Colin G. Beer

10. Appendix: A world survey of evidence for vocal learning in birds, by Donald E. Kroodsma and Jeffrey R. Baylis

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

1996. Kroodsma, D. E. and E. H. Miller (Eds.). Ecology and Evolution of Acoustic Communication in Birds. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY.

CONTENTS

PART I. DEVELOPMENT

Introduction

1. Ecology of passerine song development, by Donald Kroodsma

2. Eco-gen-actics: A systems approach to the ontogeny of avian communication, by Meredith West and Andrew King

3. Nature and its nurturing in avian vocal development, by Luis F. Baptista

4. Birdsong learning in the laboratory and field, by Michael D. Beecher

5. Acquisition and performance of song repertoires: Ways of coping with diversity and versatility, by Dietmar Todt and Henrike Hultsch

6. Acoustic communication in parrots: laboratory and field studies of budgerigars, Melopsittacus undulatus, by Susan M. Farabaugh and Robert J. Dooling

PART II. VOCAL REPERTOIRES

Introduction

7. Categorization and the design of signals; the case of song repertoires , by Andrew G. Horn and J. Bruce Falls

8. Comparative analysis of vocal repertoires, with reference to chickadees, by Jack P. Hailman and Millicent Sigler Ficken

9. Acoustic communication in a group of nonpasserines birds, the petrels, by Vincent Bretagnolle

PART III. VOCAL VARIATION IN TIME AND SPACE

Introduction

10. The population memetics of birdsong, by Alejandro Lynch

11. Song traditions in indigo buntings; origin, improvisation, dispersal , and extinction in cultural evolution, by Robert B. Payne

12. Vocalizations and speciation of palearctic birds, by Jochen Martens

13. Acoustic differentiation and speciation in shorebirds, by Edward H. Miller

14. A comparison of vocal behavior among tropical and temperate passerine birds, by Eugene S. Morton

15. Study of bird sounds in the Neotropics: urgency and Opportunity, by Donald E. Kroodsma, Jacques M. E. Vielliard, and F. Gary Stiles

PART IV. CONTROL AND RECOGNITION OF VOCALIZATIONS

Introduction

16. The neuroethology of birdsong, by Eliot A. Brenowitz and Donald E. Kroodsma

17. Organization of birdsong and constraints on performance, by Marcel M. Lambrechts

18. Bird communication in the noisy world, by Georg M. Klump

19. Sex differences in song recognition, by Laurene Ratcliffe and Ken Otter

20. Vocal recognition of neighbors by territorial passerines, by Philip Kraft Stoddard

PART V. THE BEHAVIOR OF COMMUNICATING

Introduction

21. Using interactive playback to study how songs and singing contribute to communication about behavior, by W. John Smith

22. Dynamic acoustic communication and interactive playback, by Torben Dabelsteen and Peter K. McGregor

23. Communication networks, by Peter K. McGregor and Torben Dabelsteen

24. The dawn chorus and other diel patterns in acoustic signaling, by Cynthia A. Staicer, David A. Spector, and Andrew G. Horn

25. Song and Female choice, by William A. Searcy and Ken Yasukawa

Appendix. Natural Sound Archives: Guidance for recordists and a request for cooperation, by Donald E. Kroodsma, Gregory F. Budney, Robert W. Grotke, Jacques M. E. Vielliard, Sandra L. L. Gaunt, Richard Ranft, and Olga D. Veprintseva

Literature Cited

Subject index

Taxonomic index