Contents

1) NPR’s Fresh Air with Terry Gross

2) Birdsong. A Natural History

3) NPR and National Geographic’s Radio Expeditions

4) The Diane Rehm Show

5) Earthwatch Radio

6) The Kojo Nnamdi show

7) Story Preservation Initiative

8) Scientific American

9) New Hampshire Public Television

10) Writer’s Voice

11) American Birding Association; “Birding” Interview

12) American Birding Association: Web Extra

13) Cary Institute Presentation

14) This Birding Life

15) Music for Life

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

1) NPR’s Fresh Air with Terry Gross; Understanding Birdsong— and its Fans. 3/29/2005

Listen here

Donald Kroodsma is a renowned specialist in the interpretation of bird songs. His new book, The Singing Life of Birds: The Art and Science of Listening to Birdsong, describes how birds communicate and why. But Kroodsma is also the subject of another book — about those who listen to birds.

Birdsong, by Don Stap, details the work and passions of people who analyze the sounds of birds. Stap followed Kroodsma from the lab into the field to write his account of the researcher at work.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

2) Birdsong. A Natural History.

by Don Stap

Following one of the world’s experts [Donald Kroodsma] on birdsong from the woods of Martha’s Vineyard to the tropical forests of Central America, Don Stap brings to life the  quest to unravel an ancient mystery: Why do birds sing and what do their songs mean? We quickly discover that one question leads to another. Why does the chestnut-sided warbler sing one song before dawn and another after sunrise? Why does the brown thrasher have a repertoire of two thousand songs when the chipping sparrow has only one? And how is the hermit thrush able to sing a duet with itself, producing two sounds simultaneously to create its beautiful, flutelike melody?

quest to unravel an ancient mystery: Why do birds sing and what do their songs mean? We quickly discover that one question leads to another. Why does the chestnut-sided warbler sing one song before dawn and another after sunrise? Why does the brown thrasher have a repertoire of two thousand songs when the chipping sparrow has only one? And how is the hermit thrush able to sing a duet with itself, producing two sounds simultaneously to create its beautiful, flutelike melody?

Stap’s lucid prose distills the complexities of the study of birdsong and unveils a remarkable discovery that sheds light on the mystery of mysteries: why young birds in the suborder oscines — the “true songbirds” — learn their songs but the closely related suboscines are born with their songs genetically encoded. As the story unfolds, Stap contemplates our enduring fascination with birdsong, from ancient pictographs and early Greek soothsayers, who knew that bird calls represented the voices of the gods, to the story of Mozart’s pet starling.

In a modern, noisy world, it is increasingly difficult to hear those voices of the gods. Exploring birdsong takes us to that rare place — in danger of disappearing forever — where one hears only the planet’s oldest music. – See more at the publisher’s website.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

3) NPR and National Geographic’s Radio Expeditions: Searching Out ‘The Singing Life of Birds’

by Elizabeth Arnold; June 13, 2005

Listen here

Don Kroodsma with the tools of the trade — binoculars, a powerful microphone to capture bird songs, a tape recorder slung over his left shoulder and net bags to capture and tag birds for identification

Don Kroodsma has studied the songs of birds for 30 years and is recognized as the reigning authority on the biology of bird vocal behavior. He’s written a new book about the art and science of birdsong, The Singing Life of Birds: The Art and Science of Listening to Birdsong.

His field of study may be unique, but the way he goes about his research is equally unique — Kroodsma tours the continent on his bicycle, collecting bird songs along the way. He biked completely across the nation once in 2003, and last year biked from the Atlantic shore to the Mississippi, lugging his recording equipment with him.

In the latest report for the NPR/National Geographic co-production Radio Expeditions, Elizabeth Arnold profiles perhaps the most prolific collector of birdsong in America. Kroodsma has listened to and recorded bird songs from Virginia to California, and constantly adds to his birdsong library back home in Massachusetts, where he’s professor emeritus of biology at the University of Massachusetts.

“There is no better way to hear a continent sing than by bicycle,” Kroodsma says. “You can read the minds of these birds if you simply listen… Riding a bike is just a great way to hear birds.”

Kroodsma explores the mysteries of birdsong — how birds learn to sing, why some sing and some don’t, and why songs vary from bird to bird and even from place to place. “Birds have song dialects just like we humans have dialects,” he says.

After some intense listening and study, Kroodsma concluded that, just as with people, where a bird learned a song is just as important as a bird’s genealogy. He noticed in his travels that birds of the same species but in different states sang the same song, but with their own unique “accents.”

Don Kroodsma holds a unique roadkill found on one of his bike trips — a barn owl

“The songs of birds changed just as much as the songs of people,” he says.

That led him to record not just bird sounds, but the dialect of the people he met along the way. And just like with birds, Kroodsma is confident he can tell a lot by where a person was born by the twang of a dialect.

Kroodsma’s on the road again this summer, encouraged by the people he’s met in his travels — people who listen as intently as he does to the sounds of nature.

“There’s this wonderful Zen parable,” he says. “If you listen to the thrush and hear a thrush, you’ve not really heard the thrush. But if you listen to a thrush and hear a miracle, then you’ve heard the thrush.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

4) The Diane Rehm Show: Bird Watching and Listening

8/27/2008

Listen here

A history of one of the fastest growing outdoor activities in America, and two new guides to help you identify specific birds and their songs.

Guests: Lee Allen Peterson: son of naturalist Roger Tory Peterson and author of “The Peterson Field Guide to Edible Wild Plants.”

Donald Kroodsma: a visiting fellow at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

5a) Earthwatch Radio: Singing Competition

5a) Earthwatch Radio: Singing Competition

Singing Competition; Intense competition forces male songbirds to keep their musical talents in tune.

Listen: Singing Competition

May 4, 2005

By Steve Pomplun

Why do birds sing? Donald Kroodsma is an ornithologist at the University of Massachusetts and author of a new book, “The Singing Life of Birds.” He says one reason birds sound off is to keep rivals off their turf. They usually use simple calls to do that. Kroodsma says the real vocal talent comes out when the goal is romance. Case in point: the mockingbird.

“A mockingbird that sings all night long is not so intent on defending its territory, he is advertising that he’s a bachelor. He’s unpaired and trying to attract a female. And even a paired male, when he does most of his singing is when his female is fertile.”

Kroodsma says the male needs to keep his singing sharp to maintain his partner’s interest. Because for her, it’s a case of “what have you sung for me lately.”

“They might raise a couple of broods during the year. And when the female is about to lay eggs again, she’s fertile, and that’s when he does most of his singing to try to re-impress her, because after all, she has a choice at this point. She could leave him and go to another male, she could go visit that bachelor who’s been singing all night long.”

Sometimes she does. Kroodsma says a female mockingbird will sometimes mate with others but stay with her male partner, who then unknowingly helps raise offspring fathered by a rival.

Kroodsma says the key to any female songbird’s heart lies in the male’s vocal talents.

“We hear a great quantity of singing, and a great variety of singing when the male is trying to impress the female. But we don’t actually know what the features are of the male’s song that seem to impress her.”

That’s Donald Kroodsma, author of “The Singing Life of Birds.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

5b) Earthwatch Radio: Learning to Sing

Learning to Sing; The complex vocalizations of songbirds are learned, not inherited. Some even have regional accents.

Listen here: Learning to Sing

May 10, 2005

By Steve Pomplun

Wrens, thrushes and other songbirds don’t hatch with their impressive musical talents. They learn to sing their extensive repertoires by listening to others of their kind.

Donald Kroodsma is the author of a new book, “The Singing Life of Birds.” Kroodsma says many birds seem to come naturally equipped with basic sounds and even some very simple songs. The eastern wood-pewee is an example.

“We’ve done some experiments showing that those songs are pretty much encoded in the DNA. But as a result, it’s a pretty limited repertoire of, oh, in the eastern wood peewee, of up to three different songs. But all the songbirds, when we think of songbirds, we think of wrens and warblers, robins, thrushes, sparrows, all the birds that make so much racket, these are the songbirds that have very special groups of neurons in the brain, and most of them imitate precise details of songs just like you and I learned our native language.”

Kroodsma says birds even share our tendency toward regional dialects.

“When birds learn songs at a particular location and stay around at that location, regional dialects tend to develop. They have the same kind of dialects that develop in human speech.”

Kroodsma says he recently took a long bike trip, from the Atlantic Coast through Virginia, Kentucky and Illinois. He says the accents and dialects of both people and birds changed along the way.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

5c) Earthwatch Radio: The Sounds of Biodiversity

The Sound of Biodiversity; Nature includes some complex and interesting sounds, and a bird expert wants people to appreciate their beauty and importance.

Listen here: The Sounds of Biodiversity

May 23, 2005

By Steve Pomplun

Donald Kroodsma has been listening to birds for more than 30 years. The University of Massachusetts ornithologist has written a new book called “The Singing Life of Birds.” It includes a CD of 98 recorded bird songs, with explanations for each one.

Kroodsma says we still know very little about the science of bird songs. Some are incredibly complex, and can only be fully heard by human ears when slowed to one-tenth their normal speed. And some birds have an enormous repertoire. For example, an individual brown thrasher sings more than 2,000 distinct little songs.

But many songbird species are threatened or endangered by habitat loss and other environmental hazards. Kroodsma says we’ll lose an underappreciated part of the Earth’s biological diversity if the black-capped vireo, hooded warbler and other endangered songbirds disappear.

“I think it would be an enormous pity if we lost any voice on this singing planet that we have. And some argument could be made for some dialects. There is a dialect of a solitaire in Costa Rica that is so different from other dialects, and to lose that voice from this Earth would be an enormous pity.”

Kroodsma wants people to tune in to the sounds of nature.

“It is my goal to have people walking down the road, taking their headphones off and hearing the world around them. It is just extraordinary, what’s going on around us.”

That’s Donald Kroodsma, author of “The Singing Life of Birds.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

5d) Earthwatch Radio: Beaks with a Beat

Beaks with a Beat; Some birds prefer percussion over song as a means to communicate.

Listen here: Beaks with a Beat

June 21, 2005

By Steve Pomplun

When a woodpecker hammers on a tree, it’s not always digging for insects in the bark or branches. It might be drumming out a message.

Donald Kroodsma is an ornithologist at the University of Massachusetts and author of a new book, “The Singing Life of Birds.” Kroodsma says woodpeckers often use percussion to get their point across.

“The sounds that we hear from woodpeckers I would classify in two major categories. One, the very distinctive drumming — the declaration of territory, the attempts to communicate with a member of the same or opposite sex — and the other sounds, the rapping of trees, that’s just a byproduct of foraging. When they’re drumming and communicating, it’s really not about food.”

Kroodsma says each species makes a recognizable beat. For example, here’s a downy woodpecker: (pecking sounds)

The hairy woodpecker prefers a faster tempo. (pecking sounds)

And the yellow-bellied sapsucker creates an unusual rhythm. (pecking sounds)

Most woodpeckers use simple vocalizations in addition to drumming. But Kroodsma says their most important communications come through percussion.

“I would say that the drumming that these woodpeckers do is functionally equivalent to all of the songs that these songbirds sing, it’s just not vocal, it’s a mechanical sound, but the woodpeckers have found a way to use these mechanical sounds as, I would say, songs.”

Some woodpeckers even look for trees that make a particular sound. When they want to send a message, not just any wood will do.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

6) Bird Songs: The Kojo Nnamdi show

Listen here

How do baby birds learn to sing? Do birds have regional accents or dialects? A researcher who has studied birds for more than thirty years explains how and why birds sing, and what we can learn by better understanding their songs.

Guest: Donald Kroodsma, author “The Singing Life of Birds” (Houghton Mifflin)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

7) Story Preservation Initiative

January 2014

Listen here

Preserving the Stories of Our Lives by capturing the voices, words, and meanderings of artists, scientists, writers, poets, musicians, and eyewitnesses to history. Listen, learn, and be amazed!

The Singing Life of Birds. A Conversation with Don Kroodsma

By Story Preservation Initiative on July 22, 2013

Don Kroodsma has studied birdsong for 30 years.

He has listened to and recorded bird songs from the East Coast to the West, and constantly adds to his birdsong library back home in Massachusetts, where he’s professor emeritus of biology at the University of Massachusetts.

He has listened to and recorded bird songs from the East Coast to the West, and constantly adds to his birdsong library back home in Massachusetts, where he’s professor emeritus of biology at the University of Massachusetts.

His book The Singing Life of Birds: The Art and Science of Listening to Birdsong won the 2006 John Burroughs Medal “for outstanding natural history writing” and the American Birding Association’s Robert Ridgeway Award “for excellence in publications in field ornithology.”

Kroodsma explores the mysteries of birdsong — how birds learn to sing, why some sing and some don’t, and why songs vary from bird to bird and even from place to place. “Birds have song dialects just like we humans have dialects,” he says.

After some intense listening and study, Kroodsma concluded that, just as with people, where a bird learned a song is just as important as a bird’s genealogy. He noticed in his travels that birds of the same species but in different states sang the same song, but with their own unique “accents.”

His field of study may be unique, but the way he goes about his research is equally unique — Kroodsma tours the continent on his bicycle, collecting bird songs along the way. He biked completely across the nation once in 2003, and last year biked from the Atlantic shore to the Mississippi, lugging his recording equipment with him.

“There is no better way to hear a continent sing than by bicycle,” Kroodsma says. “You can read the minds of these birds if you simply listen… Riding a bike is just a great way to hear birds.”

“There’s this wonderful Zen parable,” he says. “If you listen to the thrush and hear a thrush, you’ve not really heard the thrush. But if you listen to a thrush and hear a miracle, then you’ve heard the thrush.”

A fun site: a thrush challenge

We will be recording Don this fall.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

8) Scientific American. The Language of Song: An Interview with Donald Kroodsma

By Jennifer Uscher

Read interview here at Scientific American website, or read below

DON KROODSMA, with microphone, records and studies the songs of birds for clues to the evolution of vocal learning. Image: COURTESY OF DON KROODSMA

Young parrots, songbirds and hummingbirds learn a repertoire of songs, just as human infants learn to talk. But why is this ability to learn a vocal communication system something we share with birds, but not with our closer relatives, such as the nonhuman primates?

In the Venezuelan Andes, in search of the Merida Wren

For over 30 years, Donald Kroodsma has worked to unravel such mysteries of avian communication. Through field studies and laboratory experiments, he’s studied the ecological and social forces that may have contributed to the evolution of vocal learning.

Kroodsma has paid particular attention to local variation in song types, known as dialects. The Black-capped Chickadees (Parus atricapillus) on Martha’s Vineyard, for example, have an entirely different song than their counterparts on the Massachusetts mainland, he says. Birds that live on the boundary between two dialects or that spend time in different areas can become “bilingual,” learning the songs of more than one group of neighbors. Recently, Kroodsma discovered that the Three-wattled Bellbird (Procnias tricarunculata) is constantly changing its song, creating what he calls a “rapid cultural evolution within each generation.” This kind of song evolution is found in whales but, up until now, rarely in birds.

A professor of biology at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, Kroodsma is also co-editor of the book Ecology and Evolution of Acoustic Communication in Birds (Cornell University Press, 1996). Though he plans to continue his field studies, he says that one of his most important goals now is to help people understand how to listen to birdsong. “Many people can identify a Wood Thrush (Hylocichla mustelina) when they hear it–it’s one of the most beautiful songs in the world,” he says. “Little do they realize they could hear the things that Wood Thrush is communicating if they just knew how to listen.”

SA: Can you make any comparison between how a baby bird learns to sing and how a young human learns to speak?

DK: On the surface, it’s remarkably similar. I often play a tape of my daughter, recorded when she was about a year and a half old. She is taking all the sounds she knows¿”bow-wow, kitty, no, down”¿and randomly piecing them together in a nonsensical babbling sequence. Then I play a tape of a young bird and dissect what it¿s doing in what we call its “subsong,” and it¿s exactly the same thing. It¿s taking all the sounds it has memorized, all the sounds it has been exposed to, and singing them in a random sequence. It looks like what the baby human and the baby bird are doing is identical. Some might say that¿s a crass comparison, but it¿s very intriguing.

SA: Why do the song repertoires and dialects of some birds vary from place to place?

DK: For the species of birds that do not learn their songs, I like to think of it simplistically as the song being encoded right in their DNA. With these birds, if we find differences in their songs from place to place, it means that the DNA has changed too, that the populations are genetically different.

But there are species in which the songs are not encoded in the DNA. Then we have something very similar to humans, in which speech is learned and varies from place to place. If you were raised in Germany, for example, you¿d be speaking German rather than English with no change in your genes. So with the birds that learn their songs, you get these striking differences from place to place because the birds have learned the local dialect.

SA: How is this affected by whether a bird is nomadic?

Sedge Wren

DK: If you know the rest of your life you’re going to be speaking English, you work hard at learning English. But what if you know that you¿ll be repeatedly thrown in with people speaking different languages from all over the world? You start to see the enormous challenge it would be to learn the language or dialect of all these different locations. So I think for nomadic birds like Sedge Wrens [Cistothorus platensis] , because they are thrown together with different birds every few months from all over the geographic range, they don’t bother to imitate the songs of their immediate neighbors. They make up some kind of generalized song, or rather the instructions in their DNA allow them to improvise this very Sedge Wren-y song.

Marsh Wren

The contrast for the Sedge Wren is the closely related Marsh Wren [Cistothorus palustris]. The western Marsh Wrens, in the Seattle area or California, stay on their territory year-round. Once a male settles on a territory he learns the songs of his neighbors. They live within this very stable community, and I think that gives them the impetus to imitate each other. Why should they imitate each other and all have the same songs? I wish I knew the answer to that.

SA: One of the ways you were able to prove that song knowledge is innate–rather than learned–for certain species was by depriving young Phoebes of their ability to hear.

Eastern Phoebe

DK: We’d done a bunch of experiments, but we knew that the final step before we could declare that they do not learn was to prevent them from hearing themselves practice. So we removed the cochlea from the ears of a few Eastern Phoebes [Sayornis phoebe], and they still perfectly produced these beautiful songs. They should not have been able to develop normal songs after being deafened if there was any learning component at all.

SA: You’ve compared the Three-wattled Bellbird of Costa Rica to the Humpback whale [Megaptera novaeangliae] because their songs evolve rapidly within each generation. How have the bellbirds¿ songs changed since people started recording them?

Three-wattled Bellbird

DK: We have a series of recordings going back to the mid-1970s, giving us nice documentation of their songs in three dialects. In two of the dialects, the songs of the Seventies are drastically different from the songs today. In the third dialect, the one we¿re working with more carefully, we can plot many of the microchanges over time.

One change is a very loud whistle that has been declining in frequency [pitch] since the 1970s. The frequency has gone from about 5,500 Hz, or cycles per second, down to about 3,700 Hz. That¿s an enormous drop, and it¿s an average drop of 70 Hz per year from the 1970s to 2001.

SA: Is the Bellbird unique among birds in that its songs evolve this way?

DK: These birds are relearning their songs probably all the time as they monitor what other birds are singing. This kind of change has been found in only a couple of other birds, including the Yellow-rumped Cacique [Cacicus cela] in Panama. It¿s a blackbird and it lives in colonies. The songs within colonies change within a generation.

In birds that have fairly short lives, such as Indigo Buntings [Passerina cyanea], which live a couple of years, once the male develops his song he sticks with it throughout life. Each individual male is not constantly relearning his songs over time.

SA: Why do you think the Bellbirds¿ songs change?

DK: Probably like in most lekking systems, relatively few males are successful. The males display [before an audience of females], and many of the females agree as to which is the best male. The females are probably in charge of this system that enables males to show how long they¿ve been around, whether they¿re singing the songs of the local dialects and keeping up with the changes. So the successful males could be changing their songs, forcing the other males, especially the younger birds, to keep up with them. It may be a way for the females to be able to identify the dominant males or the ones who have been in the population the longest.

SA: And one of the ways you were able to prove that Bellbirds learn their songs is that you found they could mimic other birds.

DK: A friend told me about a city called Arapongas in Brazil. If you say “Arapongas” and emphasize the “pong,” more or less they¿re describing the song of the Bare-throated bellbird that lives in southern Brazil. The town is named after the bird.

People keep Bellbirds in cages in this town. My friend heard a caged bellbird making sounds like a Chopi blackbird [Gnorimopsar chopi] there. He found out that it had been raised with Chopi blackbirds and had learned elements¿the whistles and the purr¿of their songs. This was a nice experiment done by bird fanciers, and we were able to obtain what I see as unequivocal proof that this one bellbird learned its sounds from the blackbirds.

SA: Why do you find the Bellbird project so compelling?

DK: It¿s difficult to think objectively once you see these birds because they are so charismatic. They hop around on their perches, they square off, they push each other off perches, they scream in each other¿s ears, they stick their heads into other birds’ mouths. They¿re just extraordinary.

The reason that as a scientist I find it exciting is that this is only the fourth group of birds in which we have documented any type of vocal learning. I think they provide a window on the conditions under which vocal learning might have evolved in other groups.

SA: What mysteries of birdsong would you most want to solve in your lifetime?

DK: Why do birds acquire sounds the way they do? Why do some birds learn and some don’t? Neighboring robins seem to have dissimilar songs, and that suggests that they probably make them up. There must be some grand evolutionary blueprint by which all of these birds are operating, and if we just knew enough about their life histories, my gut feeling is that all this variety we see among birds would start to make sense.

Jennifer Uscher, a freelance science writer in New York, specializes in writing about birds.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

9) New Hampshire Public Television: Bird Tales, a television documentary

Learn here about Bird Tales

On BIRD TALES, a NHPTV Windows to the Wild special, you’ll meet Sarah Zuccarelli, who lives at a bird sanctuary in Center Sandwich, New Hampshire; Don Kroodsma, a world-famous birdsong expert from Massachusetts who’s been studying their songs for over 40 years . . . BIRD TALES is the story of people who, in unique ways, share a love for birds . . .

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

10) Writer’s Voice with Francesca Rheannon

Listen here

A 51-minute radio interview:

Birdsong by the Seasons and more

Pull up a chair. Get to know these birds. Not just as a species quickly to identify, but as individuals with lives of their own. . . . That’s birdsong expert Donald Kroodsma . . .

Host Francesca Rheannon talks with birdsong expert Donald Kroodsma about his newest book, BIRDSONG BY THE SEASONS . . .

Donald Kroodsma has been called the “reigning authority on the biology of avian vocal behavior”–birdsong. I first spoke with him in 2005 about his book, The Singing Life of Birds: The Art and Science of Listening to Birdsong, which went on to become a bestseller. Now he’s come out with BIRDSONG BY THE SEASONS. The book, along with two accompanying CDs takes the reader through a year of listening to birds, both in the author’s native listening grounds of western Massachusetts, as well as in the jungles of Costa Ricaand other places.

Kroodsma is currently a visiting fellow at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and professor emeritus at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. He’s been studying birdsong for more than 40 years.

See a sonogram and listen to the song of the lark bunting.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

11) American Birding Association; “Birding” Interview

A singing wren in his backyard started Donald Kroodsma on a career of listening to birds. In the past 40 years, Kroodsma has published widely in the scientific literature, but more recently has focused on books for the layperson. Those books include The Singing Life of Birds: The Art and Science of Listening to Birds (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2005; winner of the John Burroughs Medal), The Backyard Birdsong Guides (Chronicle Books, 2008), and most recently Birdsong by the Seasons: A Year of Listening to Birds (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009). Kroodsma is professor emeritus at the University of Massachusetts, and he was the 2006 recipient of the ABA’s Robert Ridgway Award for excellence in publications pertaining to field ornithology. He was also the 2003 recipient of the Elliot Coues Award from the American Ornithologists’ Union, by which he was cited as the reigning authority on the biology of avian vocal behavior. In this lively Birding interview, Kroodsma encourages birders to find a deeper connection with birds through their songs, explains why he prefers birding by bicycle, and talks frankly about birdsong and sex.

— Noah K. Strycker

Birding: Besides puffing air through a voice box (or two), how does a bird sing?

Donald Kroodsma: In songbirds, big interconnected hunks of the brain are dedicated to singing, and these “song control centers” are much larger in birds with bigger song repertoires (for example, a Brown Thrasher with thousands of songs) than in birds with smaller song repertoires (for example, a Chipping Sparrow with one song per male). Beginning at about two weeks of age, the young bird (usually a male) begins to memorize the song(s) of an adult and somehow stores those memories in his brain. Then he starts his practice singing. He works and works on his singing routine, practicing by babbling to get all of the neurons firing in just the right way so that the dozen or more tiny muscles controlling his two voice boxes get it just right. His perfected songs are masterpieces of precision breathing that are then announced for all the world to hear. Birdsong is truly one of the wonders of the natural world.

Birding: What do birds say in their songs? Why do they keep repeating themselves?

DK: I like to think of the non-singing female (nonsinging in most species, anyway) as the silent architect of the male’s song. Over evolutionary time, she has “designed” the male so that his songs tell her whether he is worthy to be the father of her offspring. By the mating choices she makes, she perpetuates the genes of “good singers,” with “good” being defined by something that lies deep in the female psyche of each species. He continues to sing and sing because she is listening, whether “she” is his mate or the female next door. In essence, the singing is mostly about sex. When I’m “off the record,” I tell people to think of birdsong as foreplay, but you can’t print that, of course.

Birding: How do birds learn to sing? Once they know their repertoire, do birds improvise or change their tune?

DK: Young songbirds of many species imitate songs rather precisely, so that the song(s) of the tutor and “pupil” are essentially identical. Consider dialects of White-crowned Sparrows, for example, in which all males within the dialect have much the same song; five or six such dialects might occur within in an area as small as, say, Point Reyes National Seashore, just north of San Francisco. In other species, such as the Sedge Wren or Gray Catbird, young males improvise songs, with each singer acquiring a unique repertoire of a hundred or more different songs. For most songbirds, adult males don’t seem to change their tune from one year to the next (a Florida Red-winged Blackbird I recorded in 1987 was singing the same six songs in 1992, for example). A noteworthy exception is the North- ern Mockingbird, males of which add to their song repertoires from one year to the next.

(Listen to this young Common Yellowthroat: mp3 Co Yellowthroat August babble, or this young White-throated Sparrow mp3 W-t Sparrow October babble)

Birding: What happens to birds that are not very good singers?

DK: I think that “good” is defined in each species by the female, and if he’s not singing “the right stuff,” she won’t choose him to father her offspring. The process of weeding out poor singers is thus pretty simple, as those birds leave few to no offspring. Some of the most interesting current research on birdsong is aiming to understand how the female “thinks” about male song, but so far we know little about the inner workings of her mind. (Some of my male human friends have said that about our species, too.)

Birding: What’s your favorite North American birdsong?

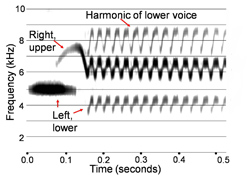

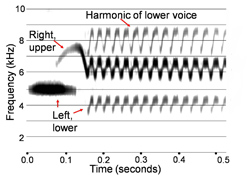

Wood Thrush: The left voice box produces the lower “song,” the right the upper

DK: That’s an especially tough question, because every species is special in its own way. In its relative simplicity, I love the song of a Henslow’s Sparrow, partly because I know when it is slowed down it is a most beautiful series of sliding whistled notes (and in slowing the song down to a fraction of normal speed, I like to believe I’m hearing the song more like the birds hear it, given their superior hearing ability). I love the magic in the Wood Thrush’s song, especially how he coordinates his two voices in the last part of the song (again, heard by us only when the song is slowed down). Or how a Hermit Thrush leaps from one song to the next, singing the next song so that it is especially different from the one he just sang. Or the wonderful complexity of a Winter Wren song. And what joy to hear Marsh Wrens argue, especially the western “species,” as males have 100 or more songs in their repertoire and often hurl identical songs back and forth at each other.

Birding: What strategies do you use as a scientist to document and interpret the meaning of bird songs? Can birders use your methods?

DK: What I do as a scientist is pretty simple. I go outside and listen (usually beginning well before sunrise). I ask (simple) questions, usually about individual birds, such as “How many songs does that Hermit Thrush have?” I record him and take the recordings back to my computer, where I use Raven software to graph the songs; you can get your free Raven-lite software online <birds.cornell.edu/brp/raven/ Raven.html>. One question leads to another, such as “Does the neighboring Hermit Thrush have the same songs?” or “How does he use his songs?” What about Hermits at other locations, or other thrushes? I often collect numbers because science is, after all, the art of collecting interesting numbers. Anyone with an inquisitive mind can have the same fun I do.

Birding: How did you get in the habit of listening to birds by bicycle? What were the best and worst parts of biking across the nation in 2003 to record bird songs?

DK: I can’t hear enough birds standing in one place, and biking allows me to cover so much more ground. In 2003, to hear this North American continent sing, I biked from Virginia to Oregon with my son David (see his website <www.rideforclimate. com> about biking to raise awareness of global warming), listening every inch of the 4,500 miles along the way. It was 10 weeks of heaven, 70 days on the road and up before sunrise every day, just listening to all the birds had to say. On the best days I’d start biking an hour or two before sunrise, energized by the symphony of light and song as it swept by during the dawn chorus. Or I’d prowl around our campsite, listening and recording during the dawn hours. So good was life on the road just listening to birds speak their minds that I returned to the University of Massachusetts that fall and told them, “I’m outta here.” I needed to listen and write about birdsong full-time, sharing the magic with all who would pay attention. The worst parts? None come to mind. Even the dogs through Kentucky were fun. (You should hear my stereo recordings of dogs chasing cyclists!)

Birding: As with acquiring human languages, do people have a special capacity in youth to learn bird vocalizations?

DK: I wouldn’t doubt it, but I know of no data to help answer the question. I didn’t start listening until I graduated from college, and what really helped my listening was making sonograms (“musical scores for birdsong”) of the songs, so that I could see what I was hearing. Now I think I listen with my eyes as much as my ears, as I see these sonograms dance across the sky as the birds sing

Birding: You write about using song to identify with birds, not just to identify birds. What do you mean by that?

DK: When I read accounts of “big days,” on which bird song is used merely to identify birds and check them off on a list, I am sad. The phrase “birding by ear” has this same connotation to me. I think of how impoverished our lives would be if we treated people the same way, checking our friends off on a list as soon as we saw or heard them at a hundred yards and then rushing on to find the next.

What I so cherish about birdsong is that, when a bird sings, he offers a window into his mind, and I want to hear what he has to say. It is the most common of birds that catches my ear, too. What is the robin doing now, or the vireo, or the Chipping Sparrow, or the Song Sparrow? How is he using his songs, or how rapidly does he move through his repertoire? I linger with individuals or revisit them from day to day through a season. By truly listening, I can know a bit of what the singer is “thinking,” and I’m a little bit closer to understanding what it is like to be the bird. And that, after all, is my ultimate goal, to try to imagine what it is like to be the bird in that moment.

Birding: Where is your research leading you next?

DK: Wherever the birds take me, and what a wonderful journey it is.When I recently encountered a Ruffed Grouse drumming in October, I spent a week with him, trying to understand what he was up to. I followed Cedar Waxwings over a year, trying to understand whether these songbirds really do lack a song. And what a joy to listen to the singing conversations between a male and female Baltimore Oriole as she sits on the nest. And did you know that the first day of spring is in fact our winter solstice? Just listen to the birds, and they’ll tell you.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

12) Birding Association: Web Extra to Accompany Interview

Follow along below, or, if you are a member of the American Birding Association, see Birding archives here (http://www.aba.org/birding/v41n3p18w1.html)

Birdsong: Topics Close to my Heart

Donald Kroodsma

Talking about birdsong, as in my interview in the current issue of Birding (May 2009, pp. 18–20), isn’t enough. You have to hear birdsong to appreciate it, of course. And for some birdsong, you just need to “see” it—in the form of sonograms—to believe it. Here are four topics dear to my heart that I’d love to share with you.

Songbirds Learn to Sing

That statement rolls off the tongue easily, but what a remarkable statement it is. Young songbirds must hear and imitate the songs of adults, and in that way they learn to sing much as we learn to speak. As a result, both human speech and birdsong occur in dialects, which are learned traditions, or culture, passed down from one generation to the next. In this learning process, both humans and birds babble. Just as we practice our speech, so the birds practice their songs.

And what fun to listen to young children and young birds working to get it right. When my daughter was a little under two years old, I captured a marvelous sequence mp3 Child babbling Track 9 TSLOB of babbling from her. (Sounds for this WebExtra are taken from the CDs that accompany my two books, The Singing Life of Birds and Birdsong by the Seasons.) She babbled what sounded to me like bow wow wow wow va wa…wee wee wee…m’ hi daddy ba ma ba wow wa wa…den da daddy daddy! da daddy bow wow wow wow…dere da ditty…hey diditty…hey daddy… nyeh…na no…down. She’s thinking of dogs and cats and the little piggy who went to market, and dad, of course, even though none of us are in the room.

In North America, many young birds begin their practice singing during August, after most adults have stopped singing for the year, and they sound much like my daughter (and each of us when we were that age) as they babble their sounds in nonsensical sequences. On a CD that comes with Birdsong by the Seasons, I provide a number of examples of this “babbling”—from such species as Red-eyed Vireo, Warbling Vireo, Black-capped Chickadee, Tufted Titmouse, Carolina Wren, House Wren, Veery, Common Yellowthroat, Song Sparrow, and Baltimore Oriole. Later, during October, when the practice is a little more advanced, you can listen to a Ruby-crowned Kinglet, a White-throated Sparrow, another Song Sparrow, and more Black-capped Chickadees. Once you know how to listen, you hear these young birds everywhere.

Winter Wren illustration by Nancy Haver, courtesy of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Try listening to the young male yellowthroat

mp3 Co Yellowthroat August babble in August. He’s down in the cattails, never to be seen, at first calling djerp djerp, giving himself away as a yellowthroat, and then butchering his attempts at his witchity-witchity song. For comparison, listen to this example of an adult song adult song.

Meanwhile, a young male Song Sparrow young Song Sparrow calls from nearby in the bushes, but by his scratchy attempts at songs you’d never know who it was. By October October, however, hear how much he has improved. And by May May of the following year, he’ll be the superb adult male singer that we all know and cherish.

I love listening to young White-throated Sparrows. The adults have such an elegant song, consisting of a few long whistles followed by the triplets, what I think of as Oh Sweet Sweet Canada Canada Canada; and as an adult, each bird perfects just one song one song. But listen to the uncertainty in this October bird October bird. He can’t get beyond the first two notes, and with them he can’t decide whether the Oh should be higher or lower than the Sweet, and only in the last attempt is there a hint of the Canada triplet.

Hermit Thrush illustration by Nancy Haver, courtesy of Houghton MIfflin Harcourt

Listen as a Hermit Thrush

Birds can hear details in their songs that we can’t. Good evidence of their ability lies in Winter Wren songs. As we listen to a western bird western bird sing (eastern birds are simpler; they are a different species, I submit), we hear a blur of rapid notes and trills, but young Winter Wrens must hear the details as sharp and crisp, because we can show in sonograms that the young birds learn to sing these details that we hear only as a blur. (Okay, okay; if you want to hear the eastern eastern species of Winter Wren in North America, I’ve included a sample of that, too.)

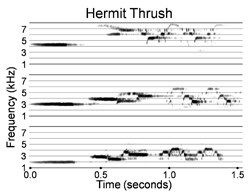

Hermit Thrush sonogram courtesy of Houghton MIfflin Harcourt

So just what do these birds hear? What is it like to hear as a Winter Wren or as a Hermit Thrush? I like to think that, as I slow down songs so that my ears can begin to hear the details, I’m beginning to hear as the bird itself hears.

Let’s try this for a Hermit Thrush. First, take a look at the three sonograms here, chosen from the dozen or so different songs that he sang. Think of them as musical scores for birdsong and they become more friendly, I think. The song begins on the left and reads across to the right, as we’d expect, and each song is a little less than a second and a half long. Now look at that beautiful whistle that begins each song; it’s about a quarter second long and held on the same pitch, or frequency. The vertical scale on the left is frequency, in thousands of cycles per second (abbreviated kHz for kilohertz, but we don’t need to worry about that term). The whistle in the top song is at 4,200 cycles per second, roughly the highest note on a piano, and the whistle of the lowest song is an octave lower, about 2,000 cycles per second; the whistle of the middle song lies in between, at 3,000 cycles per second. You can see a lot of “activity” in the last second of the song, and that’s what you need to hear, at slower speeds, to appreciate.

Now let’s listen listen. First you hear these three songs at normal speed, just as the bird sings them. Then you hear the same three songs at half speed, then at one quarter speed, and last at one-eighth speed (as speed is halved, frequency is also halved, so that the songs become both slower and lower). Go ahead, listen to the whole sequence again, and then again. As I listen in this way, eventually I become the Hermit Thrush, singing as he does, hearing as he does, and that’s a pretty special place to be. (That’s only part of the Hermit’s magic, though. He uses his repertoire of different songs in a special way to create an extraordinary performance, but that’s another story, not told here.)

Songbirds Have Two Voice Boxes

Some of the thrill that we get from hearing the Hermit Thrush’s songs at slow er speeds results from his use of two voices simultaneously. Yes, two voices. Each songbird has two voice boxes, not just one, and with two he can sing a duet with himself, singing two different songs simultaneously. And no bird does it better than the Hermit Thrush’s cousin, the Wood Thrush.

er speeds results from his use of two voices simultaneously. Yes, two voices. Each songbird has two voice boxes, not just one, and with two he can sing a duet with himself, singing two different songs simultaneously. And no bird does it better than the Hermit Thrush’s cousin, the Wood Thrush.

Wood Thrush sonogram courtesy of Houghton MIfflin Harcourt

I think of the Wood Thrush’s song as beginning with soft bup bup bup notes, but you have to be close enough to hear them. Next is the exquisite flute-like ee-o-lay phrase, with the notes delivered slowly enough that they sound wonderfully musical to our ears. Ending the song is a somewhat harsh, percussive trill or flourish that contrasts sharply with the beauty in the ee-o-lay (at least to our unaided ears). It is useful both to hear hear and see the Wood Thrush’s song.

Now let’s take a closer look and listen to that song. First, we’ll hear the ee-o-lay phrase at half speed half speed; then we’ll listen at quarter speed quarter speed. Quarter speed is best, I think, for revealing the beauty in the ee-o-lay phrases.

Wood Thrush sonogram courtesy of Houghton MIfflin Harcourt

The terminal flourish is something else. The two voices are working together so quickly here that quarter speed isn’t slow enough, so I slow them down to about one-tenth normal speed. And as I listen, I love watching the sonogram so that I can see what I’m hearing. Look at the much-expanded flourish of this Wood Thrush song, and you’ll see what he’s up to. With the air passageways through his right voice box closed, he gates air through the left voice box from the left lung, holding the tension of the membranes steady to produce a beautiful whistle held on the same frequency, all in just a little over 0.1 second. But look what happens about halfway through that whistle: He opens the passage through the right voice box, with just a little air at first (see how the sonogram isn’t as dark at first); then he first tightens the membranes slightly so that the frequency rises, and then he loosens the membranes so that the frequency falls. And the rest of the song, well, is just extraordinary, with the precision breathing and coordinating of the two voice boxes producing some of the finest sounds on the planet. With his left voice box, he produces a series of low-pitched notes that are in perfect synchrony with the higher-pitched notes from his right voice box. (The highest-pitched elements in the sonogram are a “harmonic” of the left voice box and are centered at an exact frequency multiple—8,000 cycles per second—of the “fundamental” at 4,000 cycles per second.)

Using some editing software on my computer, I can isolate these two voices so that we can hear them first in succession and then simultaneously. Now, with the sound slowed down slowed down ten times, listen first to the contribution from the left (lower-pitched) voice box, then the right, and then to the two together, as the bird sings it. Go ahead, play it again.

Ruffed Grouse illustration by Nancy Haver, courtesy of Houghton MIfflin Harcourt

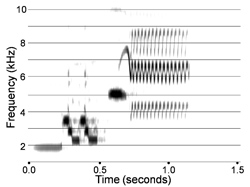

Listen to These Two Species of Ruffed Grouse

How brash of me, all by my lonesome and without consulting the official committees who are in charge of these things, to declare two species of Ruffed Grouse in North America. But I have heard them tell their story, and no one else seems to be listening. Here’s the scoop, and after listening, I’ll let you help make the call.

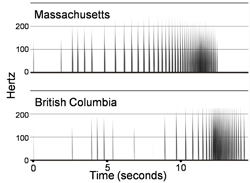

Ruffed Grouse sonogram courtesy of Houghton MIfflin Harcourt

Take a look at the two sonograms of Ruffed Grouse drums shown here. In these sonograms, each vertical mark is one wing beat, and you can see the general rhythm of the drum by the two birds; they begin slowly and end in a whir. Now look at the details. In the one from Massachusetts, the bird gradually increases the wing beat speed, rising to a peak at about 11.5 seconds; then it trails off. Now look at the drum from British Columbia; see how erratic he seems at first, to about 12 seconds; then, in a great rush he races to a peak of wing beat speed, with most of the wing beats then occurring after that peak. When seen in the sonogram, the differences are striking.

And, when listened to carefully, the differences are equally striking. Listen several times to the drum of the Massachusetts grouse Massachusetts grouse to get a feeling for the rhythm. Watch the sonogram as you listen, and you’ll see and hear the gradual increase in wing beat speed, and you’ll see and hear the symmetry in wing beat speed about that peak at 11.5 seconds.

Now brace yourself to hear the other species. To hear it, you need to go to the website of the Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Once you’re on the webpage, type 59280 into the box and click on “Find.” What you see before you now are the specifics of this particular recording number; it was made by William W. Gunn on 22 May 1962 in British Columbia. (By contacting curator Greg Budney at the Library, I learned further that this bird drummed during the afternoon at Miracle Beach Provincial Park on Vancouver Island.) Next, by clicking on the “Play” button, you can listen to this bird beating a different drum; alternatively, click on the “Visualize” button and watch the drums float across your screen as you listen. It’s an original recording, not a recording in which everything is served up neat and clean to you, so listen as if you were listening in the field, patiently (and with joy). Hear how different the rhythm is? He begins slowly, and then it’s a sudden acceleration to the peak with an extended taper of wing beat speed after that peak.

Want to listen to more Ruffed Grouse? You can take a virtual tour of Ruffed Grouse all across the continent. Go back to that first web page for the Macaulay Library and in the online archive box type “Ruffed Grouse.” Now you can choose recordings of drumming grouse from New England to Washington state. (Search the archives for other species, too, and you soon realize what a marvelous resource you have here.)

When you realize there’s only one recording of this “new species” of Ruffed Grouse, the special 59280, you may feel a bit embarrassed for me. But I’m calm. Let’s put that recording in perspective. Grouse drums are, as far as we know, “innate,” which means that the qualities of the drum are somehow encoded into the DNA. Because the genes of this one Vancouver Island grouse are no doubt like the genes of other grouse there, I’ll wager that all Vancouver Island grouse sound like this, and that further listening and recording will convince others of the existence of this second Ruffed Grouse species in the Northwest.

Here’s the challenge. Will you be traveling to Vancouver Island or more widely in British Columbia, or up to Alaska, or through Washington and Oregon west of the Cascades? Before we can settle this issue, we need recordings from other birds in this region to know how widespread these different drums are. And you don’t need high-quality recording gear to capture the rhythm of these drums, either. Let me know what you find out. Together, maybe we can report our discoveries to Birding magazine, as you can bet that thousands of birders throughout North America will be interested in the outcome of this fascinating puzzle.

I should point out that other grouse have been split recently into two species. The erstwhile Blue Grouse was recently split—re-split, actually—into two species: the Dusky and Sooty Grouse. And the bird formerly known as the Sage Grouse was recently found to consist of two species: the widespread Greater Sage-Grouse, along with the Gunnison Sage-Grouse, new to science. And much of the split was based on, you guessed it, the sounds and display features of the birds. I predict a future split in Ruffed Grouse, too, and you can be in on the fun.

Acknowledgments

For this Birding WebExtra, I offer a hearty thank you to Houghton Mifflin Harcourt for granting permission to use figures and sounds from The Singing Life of Birds: The Art and Science of Listening to Birdsong (2005) and Birdsong by the Seasons: A Year of Listening to Birds (2009). I also thank the Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology for giving permission to use the songs of the adult Common Yellowthroat, White-throated Sparrow, and western Winter Wren. Winter Wren, Hermit Thrush, Wood Thrush, Ruffed Grouse illustrations by Nancy Haver, courtesy of © Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.Hermit Thrush, Wood Thrush, and Ruffed Grouse sonograms courtesy of © Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

13) The Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies presents The Singing Life of Birds

May 6, 2011

View the hour-long presentation on the Cary Institute website

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

14) This Birding Life

Episode #13: The Singing Life of Birds

This Birding Life is a podcast from the folks at Bird Watcher’s Digest. And like the magazine’s content, the topics covered by This Birding Life range far and wide — from the backyard to the tropics, from bird feeding to bird chasing, from authors reading from their books to birders talking about their “spark” bird.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

15) Music for Life

An interview with Ryan Malone

MUSIC FOR LIFE is a music-appreciation and music-history based program that explores the purpose and value of music to humanity’s enrichment. Hosted by Ryan Malone, director of a concert series in Edmond, Oklahoma, each episode of “Music for Life” surveys the history of music, introduces its major composers and plays examples from the standard repertoire. The selections played highlight each episode’s particular theme. This interview is part of a weekly educational, music-appreciation podcast. In this session, the music of birdsong is the focus!